Overview

Teaching: min

Exercises: minQuestions

Objectives

Setup a repository for the episode

Before we can proceed we need to create a branch with some commits that we will undo in various different ways.

Exercise: Creating a branch.

- Create a new branch called

hotfix. Create a new file and make 3-4 commits in that file or create 3-4 new files. Check the log to see the hash of the last commit.Solution

git switch -c hotfix #or git checkout -b hotfix touch a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m "1st git commit: 1 file" touch b.txt git add b.txt git commit -m "2nd git commit: 2 file" touch c.txt git add c.txt git commit -m "3rd git commit: 3 file" git status git log --oneline

Amending a Git Commit message

Git Revert

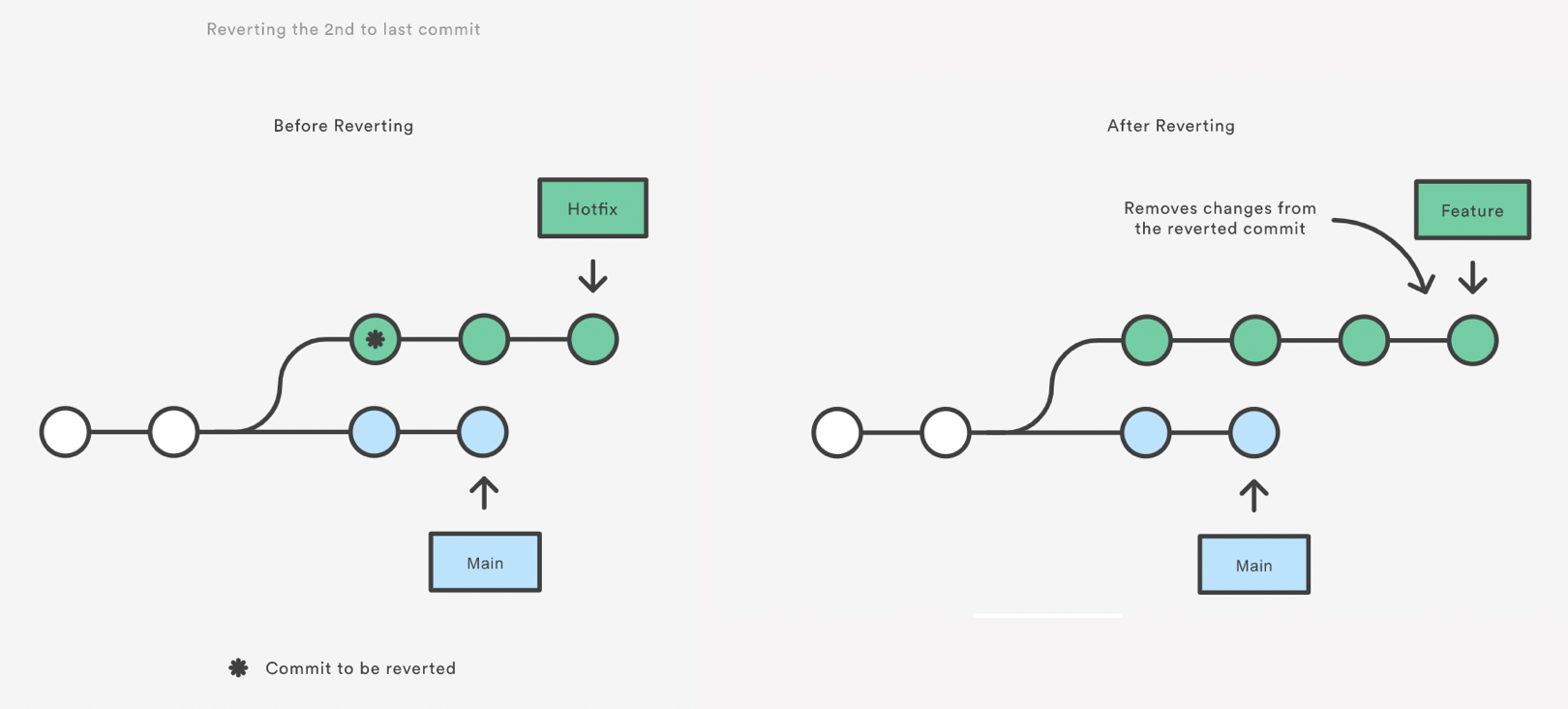

Reverting undoes a commit by creating a new commit. This is a safe way to undo changes, as it has no chance of re-writing the commit history. For example, the following command will figure out the changes contained in the 2nd to last commit, create a new commit undoing those changes, and tack the new commit onto the existing project.

git revert HEAD~1

ls

Note that revert only backs out the atomic changes of the ONE specific commit (by default, you can also give it a range of commits but we are not going to do that here, see the help).

git revert does not rewrite history which is why it is the preferred way of

dealing with issues when the changes have already been pushed to a remote

repository.

Git Reset

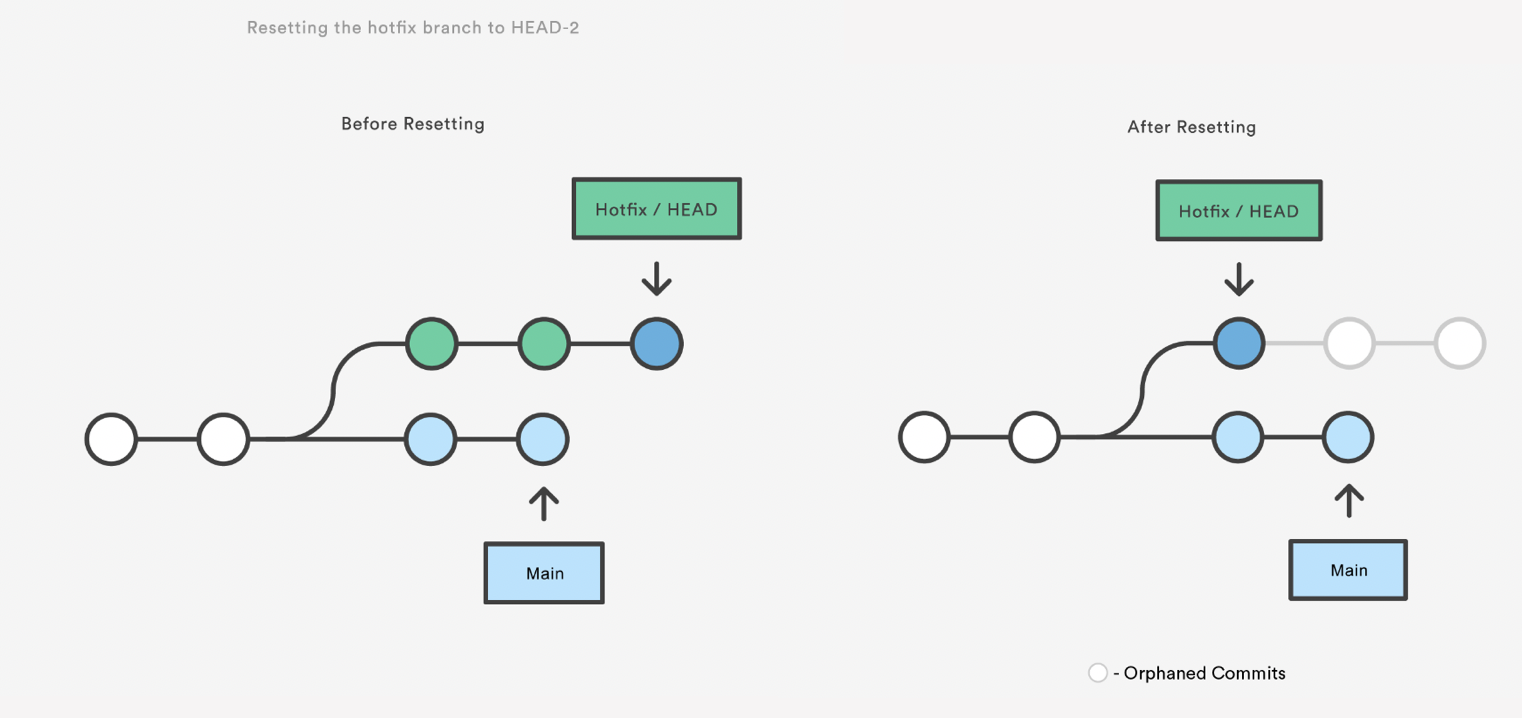

Resetting is a way to move the tip of a branch to a different commit. This can

be used to remove commits from the current branch. For example, the following

command moves the hotfix branch backwards by two commits.

git checkout hotfix

git reset HEAD~1

The two commits that were on the end of hotfix are now dangling, or orphaned commits.

This means they will be deleted the next time git performs a garbage collection.

In other words, you’re saying that you want to throw away these commits.

git reset also reverts the commits but leaves the uncommitted changes in the repo.

git status

git restore b.txt

git reset is a simple way to undo changes that haven’t been shared with anyone

else. It’s your go-to command when you’ve started working on a feature and find

yourself thinking, “Oh no, what am I doing? I should just start over.”

Using git reset on uncommitted files

In addition to moving the current branch, you can also get git reset to alter

the staged snapshot and/or the working directory by passing it one of the following flags:

–soft – The staged snapshot and working directory are not altered in any way.

–mixed – The staged snapshot is updated to match the specified commit, but the working directory is not affected. This is the default option.

–hard – The staged snapshot and the working directory are both updated to match the specified commit.

It’s easier to think of these modes as defining the scope of a git reset operation.

To just undo any uncommitted changes:

git status

git add c.txt

git status

git reset HEAD

git status

Use git restore instead of git reset for staged but uncommmitted files

The newer git restore command (as suggested by git status) can also be used

here, but you need to specify which files to unstage and that you want to unstage.

git status

git add c.txt

git restore --staged c.txt

git status

You can add and commit the changes or restore the file.

Reset a single committed file

git reset can also work on a single file:

Let’s first add some contents to our three text files.

echo "a" > a.txt

echo "b" > b.txt

echo "c" > c.txt

git add a.txt b.txt c.txt

git commit -m "added some file contents"

Now if we want to restore just one of these files to it’s previous (empty)

state we can specify it to git reset.

git reset HEAD~1 b.txt

git status

Git Checkout: A Gentle Way

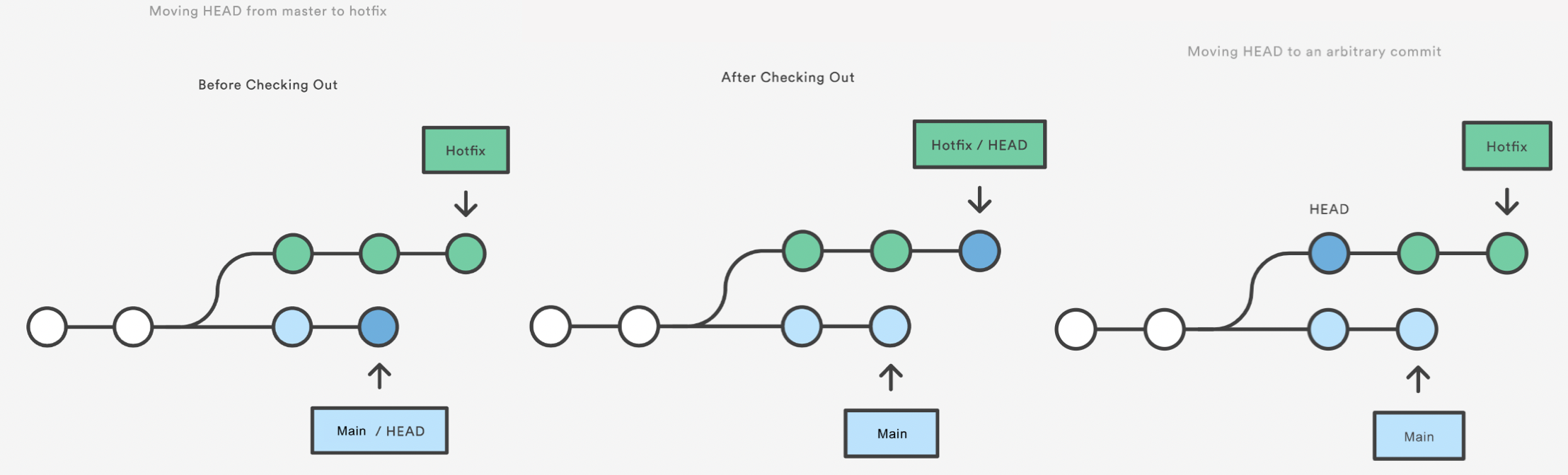

We already saw that git checkout is used to move to a different branch but is

can also be used to update the state of the repository to a specific point in

the projects history.

git checkout hotfix

git checkout HEAD~2

This puts you in a detached HEAD state. AGHRRR!

Most of the time, HEAD points to a branch name. When you add a new commit, your branch reference is updated to point to it, but HEAD remains the same. When you change branches, HEAD is updated to point to the branch you’ve switched to. All of that means that, in these scenarios, HEAD is synonymous with “the last commit in the current branch.” This is the normal state, in which HEAD is attached to a branch.

The detached HEAD state is when HEAD is pointing directly to a commit instead of a branch. This is really useful because it allows you to go to a previous point in the project’s history. You can also make changes here and see how they affect the project.

echo "Welcome to the alternate timeline, Morty!" > new-file.txt

git add new-file.txt

git commit -m "Create new file"

echo "Another line" >> new-file.txt

git commit -a -m "Add a new line to the file"

git log --oneline

If we want to keep the changes we can create another branch for them.

git branch alt-history

git checkout alt-history

If we didn’t want the changes then we can discard them and recover by switching back to the hotfix branch:

git checkout hotfix

https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/resetting-checking-out-and-reverting Also OMG: http://blog.kfish.org/2010/04/git-lola.html

Exercise: Undoing Changes

- Create a new branch called

hotfix. Create a new file and make 3-4 commits in that file. Check the log to see the hash of the last commit.Solution

git status git log

- Revert the last commit that we just inserted. Check the history.

Solution

git revert -m 1 <hash> git log

- Completely throw away the last two commits [DANGER ZONE!!!]. Check the status and the log.

Solution

git reset HEAD~2 --hard git status git log

- Undo another commit but leave it in the staging area. Check the status and log.

Solution

git reset HEAD~1 git status git log

- Wrap it up: add and commit the changes.

Solution

git add . git commit -m "Message"

Comparing hard, mixed and soft resets

So far we’ve been using the default “mixed” option for git reset. This leaves

the working directory alone and puts the files affected into the working directory.

As a reminder let’s recreate our three text files, commit them and then reset the commit to HEAD~1.

touch a.txt b.txt c.txt

git add a.txt b.txt c.txt

git commit -m "adding text files"

git reset --mixed HEAD~1

Let’s check what’s in the working directory and see what git status says.

ls

git status

and finally let’s confirm the commit is no longer there by looking at git log --oneline.

Now let’s repeat the process but this time we’ll do a soft reset. This should

leave the files staged when we run git status.

git add a.txt b.txt c.txt

git commit -m "adding text files"

git reset --soft HEAD~1

git status

Finally let’s try a hard reset. This time the files will be completely deleted

from the working directory and the repository. Since the soft reset left the

files staged there’s no need to do a git add this time.

git commit -m "adding text files"

git reset --hard HEAD~1

git status

ls

This time we see no evidence that these file ever existed, they are gone from the working directory, staging area and repository.

Challenge: When to use which type of reset?

Which reset should you use in the following scenarios:

- You have made three commits for three small changes and would prefer they were one bigger commit.

- You committed a file that you thought fixed a bug but realised soon after that you made a small mistake. You would like to fix the mistake but have the fix as a single commit.

- You have committed a file which was accidentally placed in your Git working directory and should have never been there.

Solution

- soft, we are assuming we do git reset HEAD~3`, all three files are now placed in the staging area and a single new commit will commit all three together.

- mixed, as we need to make some changes after resetting the commit we don’t want the file added to the staging area. Although we could do a soft reset followed by another

git add.- hard, since we don’t want to keep the file after the reset.

Back in time

You can restrict the action of reset to a file with:

git reset -- filenameMake some changes to a file, add that file to the staging area, and use git reset to undo the action of git add.

Solution

Add changes to a file with

$ git add <file>then reset the files with

$ git reset -- <file>or

$ git reset HEAD -- <file>or

git reset HEAD -- <file>Note how if we leave out HEAD, then git will assume we want to pull from the HEAD reference by default.

Without a HEAD

What happens if we do a hard reset, but leave out the place to copy files from, like this

$ git reset --hardCan you work out where the files come from Hint: it may help to make some changes to the files in the current directory first.

Solution

If the origin of the files is not specified, it is assumed to be HEAD by default.

Checkout on files

The checkout command from earlier has an important variant when passed files as arguments. In this case they behaves very differently. Let’s reset our repository to the way it is on the remote server to begin with.

$ git reset --hard origin/main

Let’s make two changes, one to plot_buoys.py and one to README.md. In both

cases add a line to the file listing yourself as an author of the file. In

the Python file this will need to be a comment. Go ahead and add/commit both

changes in a single commit.

$ nano README.md

$ nano plot_buoys.py

$ git add README.md plot_buoys.py

$ git commit -m "Adding author information"

Now, let’s perform a checkout, specifying that we’d like the last version of the Python file.

$ git checkout HEAD~1 -- plot_buoys.py

What happened? Previously checkout would have moved HEAD.

$ git log --oneline

We’re still on the same commit, HEAD hasn’t moved at all this time. It doesn’t make sense to move HEAD for some files and keep it in the same place for others, that would get confusing very quickly. Only the file copy operations have been performed. Let’s see what effect this has had.

$ git status

The file plot_buoys.py has been copied from the previous commit HEAD~1

into both our working directory as well and into the staging area.

We can verify the changes with

$ git diff --staged

The file plot_buoys.py has changed and nothing else has. In this case git

checkout with a file behaves very much like we would expect git reset --hard

to behave with files. It overrides the file in the staging area and working

directory and resets any changes. For this reason

$ git reset --hard HEAD~1 -- plot_buoys.py

This is not a valid command, since it would perform the same operation as the git checkout command.

Reset with files

Using git reset with files allow us to copy specific files to and from the staging area, leaving the working directory unchanged.

Let’s reset our repository to the way it was at the beginning of this lesson

$ git reset --hard origin/main

Let’s make some changes to README.md

$ nano README.md

and copy them to the staging area.

$ git add README.md

$ git status

We can use git reset to copy the version in the repository back, effectively undoing the add.

We can unstage the file with

$ git reset HEAD -- README.md

More recently (as of Git 2.23 in August 2019) the git restore command has been

introduced which can also be used to unstage changes and is suggested by

git status. Older versions of git suggested the use of git reset.

The equivalent git restore command for the above would have been:

$ git restore README.md

But you may still find a lot of Git tutorials suggesting the use of git reset

in this scenario. Either command will work.

The dangers of checkout

What happens if you make some modification to README.md, add these changes to the staging area with

$ git add README.mdand then try to checkout the file with

$ git checkout HEAD -- README.mdCan you guess what will happen? Is this potentially dangerous to do?

Solution

The command

$ git checkout HEAD -- <filename>will overwrite the file filename, even if there are changes. Be careful as you can lose your changes in this way. This command is a useful way to undo any changes you may have made to the files in your working directory.

The way things were

Can you use the checkout command to create a commit which contains the file README.md as it was 3 commits ago? Hint: because some work in the history was done on a pull request HEAD~3 might not get what you expect, use the commit hash instead.

Solution

HEAD~1 actually takes us all the way back to the first commit in the repository, even though there are 3 prior commits in the history.

git log --graph --onelinewill reveal that some of the history came from another branch and using HEAD~N doesn’t cover the commits from the branch, but treats them as if they were one commit. Let’s usegit logto find a commit hash instead.$ git log --oneline 116cdda (HEAD -> main, origin/main, origin/HEAD, hotfix) Merge pull request #1 from NOC-OI/create_initial_script 7a760ff Add some basic instructions to the README and credit to the Intermediate Python Course 6c388d0 Tidy up formatting a62d779 Write first draft of script to plot buoy locations around UK 6d4fb54 Initial commitSo let’s take commit hash a62d instead. The file can be brought into the current directory with

$ git checkout 6b4f -- README.mdAll that remains is to create a new commit, with a command such as

$ git commit -m 'README.md as it was 3 commits ago'

Without a HEAD

Can you work out what the following command does

$ git checkout -- README.mdHint: try making some changes to README.md and running the command.

Solution

This command will revert the file README.md to the state it is in the current commit. This is equivalent to running

$ git checkout HEAD -- README.mdIf the commit is not specified, git defaults to using HEAD.

Key Points