Introduction

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What do I do when I need to make complex decisions with my git respository?

How do I collaborate on a software project with others?

Objectives

Understand the range of functionality that exists in git.

Understand the different challenges that arrise with collaborative projects.

Git Refresher

Git is a version control system for tracking changes in computer files and coordinating work on those files among multiple people. It is primarily used for source code management in software development but it can be used to track changes in files in general - it is particularly effective for tracking text-based files (e.g. source code files, CSV, Markdown, HTML, CSS, Tex, etc. files).

Git has several important characteristics:

- support for non-linear development allowing you and your colleagues to work on different parts of a project concurrently,

- support for distributed development allowing for multiple people to be working on the same project (even the same file) at the same time,

- every change recorded by Git remains part of the project history and can be retrieved at a later date, so even if you make a mistake you can revert to a point before it.

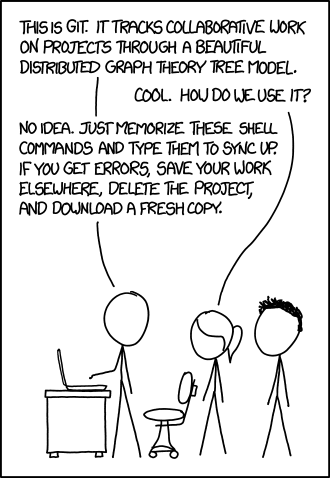

It uses a distributed version control model (the “beautiful graph theory tree model”), meaning that there is no single central repository of code. Instead, users share code back and forth to synchronise their repositories, and it is up to each project to define processes and procedures for managing the flow of changes into a stable software product.

Git is powerful and flexible to fit a wide range of use cases and workflows from simple projects written by a single contributor to projects that are millions of lines and have hundreds of co-authors. Furthermore, it does a task that is quite complex. As a result, many users may find it challenging to navigate this complexity. While committing and sharing changes is fairly straightforward, for instance, but recovering from situations such as accidental commits, pushes or bad merges is difficult without a solid understanding of the rather large and complex conceptual model. Case in point, three of the top five highest voted questions on Stack Overflow are questions about how to carry out relatively simple tasks: undoing the last commit, changing the last commit message, and deleting a remote branch.

Mouse-over text: If that doesn’t fix it, git.txt contains the phone number of a friend of mine who understands git. Just wait through a few minutes of ‘It’s really pretty simple, just think of branches as…’ and eventually you’ll learn the commands that will fix everything.

With this lesson our goal is to give a you a more in-depth understanding of the conceptual model of git, to guide you through increasingly complex workflows and to give you the confidence to participate in larger projects.

The diagram below shows a typical software development lifecycle with Git (in our case starting from making changes in a local branch that “tracks” a remote branch) and the commonly used commands to interact with different parts of the Git infrastructure, including:

- working tree -

a local directory (including any subdirectories) where your project files live

and where you are currently working.

It is also known as the “untracked” area of Git or “working directory”.

Any changes to files will be marked by Git in the working tree.

If you make changes to the working tree and do not explicitly tell Git to save them -

you will likely lose those changes.

Using

git add filenamecommand, you tell Git to start tracking changes to filefilenamewithin your working tree. - staging area (index) -

once you tell Git to start tracking changes to files

(with

git add filenamecommand), Git saves those changes in the staging area on your local machine. Each subsequent change to the same file needs to be followed by anothergit add filenamecommand to tell Git to update it in the staging area. To see what is in your working tree and staging area at any moment (i.e. what changes is Git tracking), run the commandgit status. - local repository -

stored within the

.gitworking tree of your project locally, this is where Git wraps together all your changes from the staging area and puts them using thegit commitcommand. Each commit is a new, permanent snapshot (checkpoint, record) of your project in time, which you can share or revert to. - remote repository -

this is a version of your project that is hosted somewhere on the Internet

(e.g., on GitHub, GitLab or somewhere else).

While your project is nicely version-controlled in your local repository,

and you have snapshots of its versions from the past,

if your machine crashes - you still may lose all your work. Furthermore, you cannot

share or collaborate on this local work with others easily.

Working with a remote repository involves pushing your local changes remotely

(using

git push) and pulling other people’s changes from a remote repository to your local copy (usinggit fetchorgit pull) to keep the two in sync in order to collaborate (with a bonus that your work also gets backed up to another machine). Note that a common best practice when collaborating with others on a shared repository is to always do agit pullbefore agit push, to ensure you have any latest changes before you push your own.

Git Version Control Tool

To test your Git installation, type:

$ git help

If your Git installation is working you should see something like:

usage: git [-v | --version] [-h | --help] [-C <path>] [-c <name>=<value>]

[--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path] [--man-path] [--info-path]

[-p | --paginate | -P | --no-pager] [--no-replace-objects] [--bare]

[--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>] [--namespace=<name>]

[--config-env=<name>=<envvar>] <command> [<args>]

These are common Git commands used in various situations:

start a working area (see also: git help tutorial)

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

work on the current change (see also: git help everyday)

add Add file contents to the index

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

restore Restore working tree files

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

examine the history and state (see also: git help revisions)

bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

grep Print lines matching a pattern

log Show commit logs

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

grow, mark and tweak your common history

branch List, create, or delete branches

commit Record changes to the repository

merge Join two or more development histories together

rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

switch Switch branches

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

collaborate (see also: git help workflows)

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

'git help -a' and 'git help -g' list available subcommands and some

concept guides. See 'git help <command>' or 'git help <concept>'

to read about a specific subcommand or concept.

See 'git help git' for an overview of the system.

When you use Git on a machine for the first time, you need to configure a few things:

- your name,

- your email address (the one you used to open your GitHub account with, which will be used to uniquely identify your commits),

- preferred text editor for Git to use (e.g.

nanoor another text editor of your choice), - whether you want to use these settings globally (i.e. for every Git project on your machine).

This can be done from the command line as follows:

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

$ git config --global user.email "name@example.com"

$ git config --global core.editor "nano -w"

GitHub Account

GitHub is a free, online host for Git repositories that you will use during the course to store your code in so you will need to open a free GitHub account unless you do not already have one.

Secure Access To GitHub Using Git From Command Line

In order to access GitHub using Git from your machine securely, you need to set up a way of authenticating yourself with GitHub through Git. The recommended way to do that for this course is to set up SSH authentication - a method of authentication that is more secure than sending passwords over HTTPS and which requires a pair of keys - one public that you upload to your GitHub account, and one private that remains on your machine.

GitHub provides full documentation and guides on how to:

A short summary of the commands you need to perform is shown below.

To generate an SSH key pair, you will need to run the ssh-keygen command from your command line tool/GitBash

and provide your identity for the key pair (e.g. the email address you used to register with GitHub)

via the -C parameter as shown below.

Note that the ssh-keygen command can be run with different parameters -

e.g. to select a specific public key algorithm and key length;

if you do not use them ssh-keygen will generate an

RSA

key pair for you by default.

GitHub now recommends that you use a newer cryptographic standard (such as EdDSA variant algorithm Ed25519),

so please be sure to specify it using the -t flag as shown below.

It will also prompt you to answer a few questions -

e.g. where to save the keys on your machine and a passphrase to use to protect your private key.

Pressing ‘Enter’ on these prompts will get ssh-keygen to use the default key location (within

.ssh folder in your home directory)

and set the passphrase to empty.

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your-github-email@example.com"

Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/Users/<YOUR_USERNAME>/.ssh/id_ed25519):

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Enter same passphrase again:

Your identification has been saved in /Users/<YOUR_USERNAME>/.ssh/id_ed25519

Your public key has been saved in /Users/<YOUR_USERNAME>/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:qjhN/iO42nnYmlpink2UTzaJpP8084yx6L2iQkVKdHk your-github-email@example.com

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ED25519 256]--+

|.. .. |

| ..o A |

|. o.. |

| .o.o . |

| ..+ = B |

| .o = .. |

|o..X *. |

|++B=@.X |

|+*XOoOo+ |

+----[SHA256]-----+

Next, you need to copy your public key (not your private key - this is important!) over to

your GitHub account. The ssh-keygen command above will let you know where your public key is saved (the file should have the

extension “.pub”), and you can get its contents (e.g. on a Mac OS system) as follows:

$ cat /Users/<YOUR_USERNAME>/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

ssh-ed25519 AABAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAICWGVRsl/pZsxx85QHLwSgJWyfMB1L8RCkEvYNkP4mZC your-github-email@example.com

Copy the line of output that starts with “ssh-ed25519” and ends with your email address (it may start with a different algorithm name based on which one you used to generate the key pair and it may have gone over multiple lines if your command line window is not wide enough).

Finally, go to your GitHub Settings -> SSH and GPG keys -> Add New page to add a new SSH public key. Give your key a memorable name (e.g. the name of the computer you are working on that contains the private key counterpart), paste the public key from your clipboard into the box labelled “Key” (making sure it does not contain any line breaks), then click the “Add SSH key” button.

Now, we can check that the SSH connection is working:

$ ssh -T git@github.com

What About Passwords?

While using passwords over HTTPS for authentication is easier to setup and will allow you read access to your repository on GitHub from your machine, it alone is not sufficient any more to allow you to send changes or write to your remote repository on GitHub. This is because, on 13 August 2021, GitHub has strengthened security requirements for all authenticated Git operations. This means you would need to use a personal access token instead of your password for added security each time you need to authenticate yourself to GitHub from the command line (e.g. when you want to push your local changes to your code repository on GitHub). While using SSH key pair for authentication may seem complex, once set up, it is actually more convenient than keeping track of/caching your access token.

Key Points

Git version control records text-based differences between files.

Each git commit records a change relative to the previous state of the documents.

Git has a range of functionality that allows users to manage the changes they make.

This complex functionality is especially useful when collaborating on projects with others