Content from Python Fundamentals

Last updated on 2026-02-04 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- “What basic data types can I work with in Python?”

- “How can I create a new variable in Python?”

- “Can I change the value associated with a variable after I create it?”

- “How do I use a function?”

Objectives

- “Perform simple calculations.”

- “Assign values to variables.”

- “Understand the difference between int, float and str data types.”

- “Use the print and type built-in functions.”

Variables

Python can be used as a calculator:

OUTPUT

23This is great but not very interesting. To do anything useful with

data, we need to assign its value to a variable. In Python, we

can assign a value to a variable using the equals sign

=. For example, we can track the weight of a patient who

weighs 60 kilograms by assigning the value 60 to a variable

weight_kg:

From now on, whenever we use weight_kg, Python will

substitute the value we assigned to it. In layperson’s terms, a

variable is a name for a value.

In Python, variable names:

- can include letters, digits, and underscores

- cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive.

This means that, for example:

-

weight0is a valid variable name, whereas0weightis not -

weightandWeightare different variables

Types of data

Python knows various types of data. Three common ones are:

- integer numbers

- floating point numbers, and

- strings.

In the example above, variable weight_kg has an integer

value of 60. If we want to more precisely track the weight

of our patient, we can use a floating point value by executing:

To create a string, we add single or double quotes around some text. To identify and track a patient throughout our study, we can assign each person a unique identifier by storing it in a string:

Using Variables in Python

To change the value of the weight_kg variable, we have

to assign weight_kg a new value using the

equals = sign:

Once we have data stored with variable names, we can make use of it in calculations. We may want to store our patient’s weight in pounds as well as kilograms:

We might decide to add a prefix to our patient identifier:

Built-in Python functions

To carry out common tasks with data and variables in Python, the

language provides us with several built-in functions. To display information to

the screen, we use the print function:

OUTPUT

143.0

inflam_001When we want to make use of a function, referred to as calling the

function, we follow its name by parentheses. The parentheses are

important: if you leave them off, the function doesn’t actually run!

Sometimes you will include values or variables inside the parentheses

for the function to use. In the case of print, we use the

parentheses to tell the function what value we want to display. We will

learn more about how functions work in later episodes.

We can display multiple things at once using only one

print call:

OUTPUT

inflam_001 weight in kilograms: 65.0We can also call a function inside of another function call. For example,

Python has a built-in function called type that tells you a

value’s data type:

OUTPUT

<class 'float'>

<class 'str'>Variables as Sticky Notes

A variable in Python is analogous to a sticky note with a name written on it: assigning a value to a variable is like putting that sticky note on a particular value.

Using this analogy, we can investigate how assigning a value to one

variable does not change values of other, seemingly

related, variables. Let’s look at the creation of the

weight_lb variable as an example:

PYTHON

weight_lb = 2.2 * weight_kg

print('weight in kilograms:', weight_kg, 'and in pounds:', weight_lb)OUTPUT

weight in kilograms: 65.0 and in pounds: 143.0As above, the expression 2.2 * weight_kg is evaluated to

143.0, and then this value is assigned to the variable

weight_lb (i.e. the sticky note weight_lb is

placed on 143.0). At this point, each variable is “stuck”

to completely distinct and unrelated values.

Let’s now change weight_kg:

PYTHON

weight_kg = 100.0

print('weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg, 'and weight in pounds is still:', weight_lb)OUTPUT

weight in kilograms is now: 100.0 and weight in pounds is still: 143.0Since weight_lb doesn’t “remember” where its value comes

from, it is not updated when we change weight_kg.

Comments in Python

Everything in a line of code following the ‘#’ symbol is a comment that is ignored by Python. Comments allow programmers to leave explanatory notes for other programmers or their future selves. As an example:

OUTPUT

`mass` holds a value of 47.5, `age` does not exist

`mass` still holds a value of 47.5, `age` holds a value of 122

`mass` now has a value of 95.0, `age`'s value is still 122

`mass` still has a value of 95.0, `age` now holds 102- “Basic data types in Python include integers, strings, and floating-point numbers.”

- “Use

variable = valueto assign a value to a variable in order to record it in memory.” - “Variables are created on demand whenever a value is assigned to them.”

- “Use

print(something)to display the value ofsomething.” - Functions take zero or more parameters that send a value or variable to the code in the function to use.

- “Built-in functions are always available to use.”

Content from Loading and Analyzing Argo Float Data

Last updated on 2026-02-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

Objectives

- “Explain what a library is and what libraries are used for.”

- “Import a Python library and use the functions it contains.”

- “Select individual values from data.”

- “Perform operations on arrays of data.”

Words are useful, but what’s more useful are the sentences and stories we build with them. Similarly, while a lot of powerful, general tools are built into Python, specialized tools built up from these basic units live in libraries that can be called upon when needed.

Loading data with ArgoPy

All of the data recorded by Argo floats is sent to a Data Assembly

Centre (DAC). After some checks of the data have been made it is sent to

a Global Data Assembly Centre (GDAC). There are two of these, one in the

USA and one in France, but they both hold a copy of all of the Argo data

ever received. To make accessing the data easy from Python a special

library called argopy has been developed. This can load

data directly from one of the GDACs and turn it into a Numpy array. This

saves us having to search through the GDAC, picking the data we want and

downloading it to a file on our computer.

To tell Python that we’d like to start using argopy, we

need to import it:

Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to the basic Python package, much like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Just like in the lab, importing too many libraries can sometimes complicate and slow down your programs - so we only import what we need for each program.

The argopy library has a lot of different features, but

we want to use the DataFetcher function which gets data

from a GDAC. The ArgoDataFetcher will return something

called a class that has more functions we can call. One of these is

called profile and that gets an individual profile given a

float number and a profile number. We’re going to look at data from

profile 12 of float number 6902746.

The expression argopy.DataFetcher().profile(....) is a

function call that asks

Python to run the function

profile which belongs to the DataFetcher class

which, in turn, belongs to the argopy library. The dot

notation in Python is used most of all as an object attribute/property

specifier or for invoking its method. object.property will

give you the object.property value, object_name.method()

will invoke an object_name method.

Functions, Parameters and Return Values

- In the last episode we looked at using the

printandtypefunctions which are built into Python. - We “call” a function by writing its name followed by a

(, then we can give the values of any parameters that the function might need. If there is more than one of these we separate each of them with a comma. Finally we write a closing)to end the function call.

- Parameters have to be given in the order the function expects them.

Alternatively we can put a name in front of each paraemter followed by

an

=sign and the parameter value or the name of the variable we are sending.

- Functions can also send data back to the code which called them, this is known as “returning” data from a function.

- We can save this return data into a variable to use it again later. If we don’t save it into a variable then its value is displayed on the screen.

- When we import a library like

argopymore functions become available to us.

argopy.DataFetcher().profile has two parameters: a float number and a

profile number.

If we run the profile function with the float number and profile

number we get back a datafetcher.erddap object.

OUTPUT

<datafetcher.erddap>

Name: Ifremer erddap Argo data fetcher for floats

API: https://erddap.ifremer.fr/erddap/

Domain: phy;WMO6902746

Performances: cache=False, parallel=False

User mode: standard

Dataset: phyThis doesn’t contain much useful data, although it does tell us which

GDAC supplied the data. To get the actual data we need to call yet

another function that the datafetcher.erdapp object

provides called to_xarray. This gets the data ready for

processing using another library called Xarray, which works well with

array based data but is very good at working with really big

datasets.

Now we get a lot more information including a list of what data variables this float has.

Not All Functions Have Input

Generally, a function uses inputs to produce outputs. However, some

functions produce outputs without needing any input. These functions

don’t need any parameters, so we just write () after the

function name.

For example, checking the current time doesn’t require any input.

OUTPUT

Sat Mar 26 13:07:33 2016We still need parentheses (()) to tell Python to go and

do something for us.

To get one of those we add its name to the end of the command; for

example, to get temperature we add .TEMP.

Now, to access just the array of temperature values, we add

.values on the end (note that there’s no brackets on this

as this is a variable name not a function).

Since we haven’t told it to do anything else with the function’s output, the notebook displays it. In this case, that output is the data we just loaded.

Our call to argopy.DataFetcher().profile read our file

but didn’t save the data in memory. To do that, we need to assign the

array to a variable. In a similar manner to how we assign a single value

to a variable, we can also assign an array of values to a variable using

the same syntax. Let’s capture this into a variable called

temp_data.

This statement doesn’t produce any output because we’ve assigned the

output to the variable temp_data. If we want to check that

the data have been loaded, we can print the variable’s value:

Now we have a an array with our temperature data.

Let’s check its type.

OUTPUT

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>The output tells us that temp_data currently refers to a

NumPy array, the functionality for which is provided by the NumPy

library. (The type of

argopy.DataFetcher().profile(6902746, 12).to_xarray().TEMP

is xarray.DataArray.)

NumPy, like argopy is a

Python library. It stands for Numerical Python. In general, you should

use this library when you want to do fancy things with lots of numbers,

especially if you have matrices or arrays.

These data correspond to Argo float data. Each row represents one reading and the columns are the different data values.

Data Type

A Numpy array contains one or more elements of the same type. The

type function will only tell you that a variable is a NumPy

array but won’t tell you the type of thing inside the array. We can find

out the type of the data contained in the NumPy array.

OUTPUT

float32This tells us that the NumPy array’s elements are floating-point numbers.

With the following command, we can see the array’s shape:

OUTPUT

(108,)The output tells us that the temp_data array variable

contains 108 elements in a 1D array.

If we want to get a single number from the array, we must provide an index in square brackets after the variable name, just as we do in math when referring to an element of a matrix.

OUTPUT

first temperature value: 28.898OUTPUT

middle temperature value: 9.876The expression temp_data[53] accesses the 54th element,

not the 53rd as you might think. Programming languages like Fortran,

MATLAB and R start counting at 1 because that’s what human beings have

done for thousands of years. Languages in the C family (including C++,

Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0 because it represents an offset

from the first value in the array (the second value is offset by one

index from the first value). This is closer to the way that computers

represent arrays (if you are interested in the historical reasons behind

counting indices from zero, you can read Mike

Hoye’s blog post).

Explore the data

If you haven’t already, write some Python code to load in the data from profile 12 of float number 6902746. What is the last salinity value? (Salinity is called PSAL, as temperature was called TEMP.)

Analyzing data

NumPy has several useful functions that take an array as input to

perform operations on its values. If we want to find the average of all

our Argo float data, for example, we can ask NumPy to compute

temp_data’s mean value:

OUTPUT

13.058639mean is a function

that takes an array as an argument.

Let’s use two other NumPy functions to get some descriptive values about the temperature range.

PYTHON

maxval = numpy.max(temp_data)

minval = numpy.min(temp_data)

print('Max temperature:', maxval)

print('Min temperature:', minval)Here we’ve assigned the return value from

numpy.max(data) to the variable maxval and the

value from numpy.min(data) to minval. Note

that we used maxval, rather than just max -

it’s not good practice to use variable names that are the same as Python

keywords or fuction names.

OUTPUT

Max temperature: 28.907

Min temperature: 3.693Getting help on functions

How did we know what functions NumPy has and how to use them? If you

are working in IPython or in a Jupyter Notebook, there is an easy way to

find out. If you type the name of something followed by a dot, then you

can use tab completion

(e.g. type numpy. and then press Tab) to see a

list of all functions and attributes that you can use. After selecting

one, you can also add a question mark (e.g. numpy.abs?),

and IPython will return an explanation of the method! This is the same

as doing help(numpy.abs).

Find the temperature range for an Arctic float

The float 5906983 has been deployed in the Arctic by NOC for the MetOffice. You can see a map of where it’s been at https://fleetmonitoring.euro-argo.eu/float/5906983.

Adapt the code above to load profile number 33 from float 5906983. Calculate it’s minimum, maximum, mean and median temperature.

We haven’t calculated median before, search on the internet or look at the NumPy documentation (https://numpy.org/devdocs/reference/routines.statistics.html) to find out how to calculate this.

PYTHON

temperatures = argopy.DataFetcher().profile(5906983, 33).to_xarray().TEMP.values

maxval = numpy.max(temperatures)

minval = numpy.min(temperatures)

meanval = numpy.mean(temperatures)

medianval = numpy.median(temperatures)

print('Max temperature:', maxval)

print('Min temperature:', minval)

print('Mean Temperature:', meanval)

print('Median Temperature:', medianval)OUTPUT

Max temperature: 7.463699817657471

Min temperature: -0.6674000024795532

Mean Temperature: 2.9974963312872487

Median Temperature: 3.9305999279022217- “Import a library into a program using

import libraryname.” - “The

argopylibrary can load Argo float data over the internet from the GDAC” - “Use the

numpylibrary to work with arrays in Python.” - “The expression

array.shapegives the shape of an array.” - “Use

array[x]to select a single element from a 1D array.” - “Array indices start at 0, not 1.”

- “Use

numpy.mean(array),numpy.max(array), andnumpy.min(array)to calculate simple statistics.”

Content from Visualizing Argo Data

Last updated on 2026-02-02 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- “How can I visualize tabular data in Python?”

- “How can I group several plots together?”

Objectives

- “Plot simple graphs from data.”

- “Plot multiple graphs in a single figure.”

- “Use Argopy’s plotting functions.”

Visualizing data

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of

computing is insight, not numbers,” and the best way to develop insight

is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire lecture of

its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s

matplotlib library here. While there is no official

plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto

standard. First, we will import the pyplot module from

matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and

display a line graph of our data:

Ensuring we have Loaded the Data

Let’s load some temperature, pressure and salinity data with Argopy.

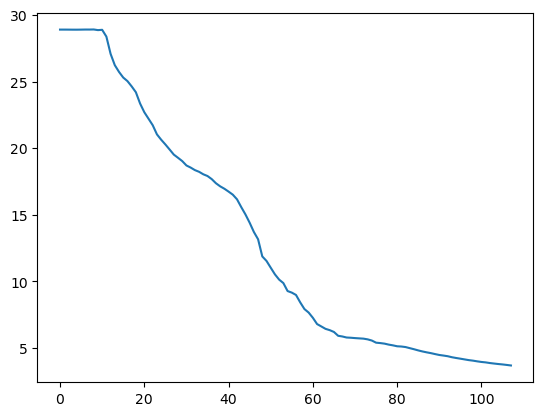

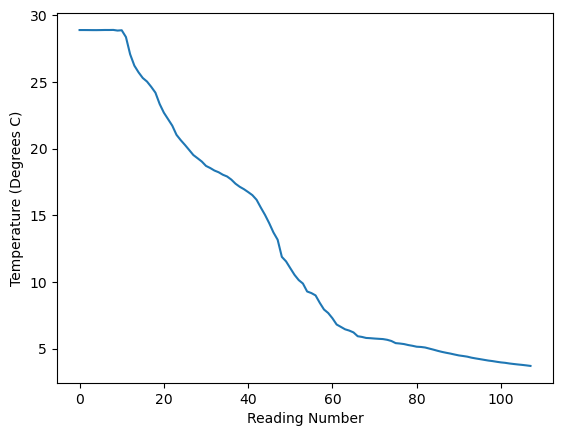

Graphing Temperature Data

Let’s use the Matplotlib library to plot this data. We’ll need to

import from the matplotlib.pyplot library. We can then use

pyplot’s plot function to plot the temperature data.

The X axis corresponds to each row in the data and the Y axis is temperature in degrees celcius.

Adding Labels to a Graph

It’s good practice to add axes labels to our graphs, these can be

done with the xlabel and ylabel functions in

matplolib.pyplot.

PYTHON

matplotlib.pyplot.ylabel("Temperature (Degrees C)")

matplotlib.pyplot.xlabel("Reading Number")

temperature_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(temperature)

Plot the pressure data

Create a plot showing the pressure (depth) across a Argo profile.

Plot using Argopy

Instead of calling functions in Matplotlib we can also call some plotting functions within Argopy (and these will call Matplotlib for us). This offers two advantages:

- we don’t need to import matplolib ourselves.

- there are some Argo specific plots available within Argopy.

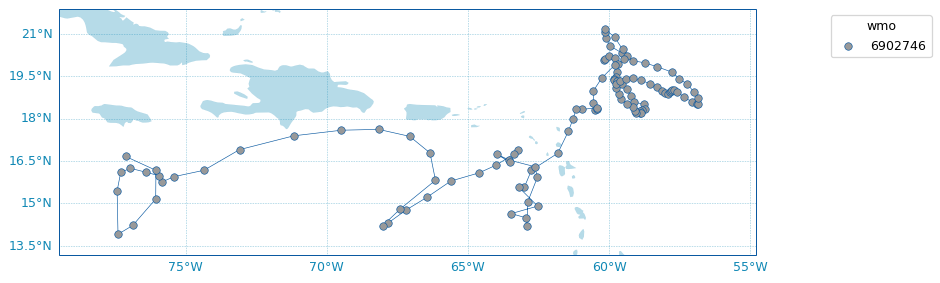

Plotting a Map of Where our Float has Travelled

One of the plots that Argopy can generate is a map showing the position of the float every time it surfaced.

PYTHON

float_data = argopy.DataFetcher().float(6902746).load()

argopy.plot.scatter_map(float_data.index, set_global=False)

You can also see the same data on an interactive map at https://fleetmonitoring.euro-argo.eu/float/6902746. For some reason the data returned by ArgoPy for this float is limted to the first 118 profiles and there are a few more after that being shown on the fleetmonitoring website.

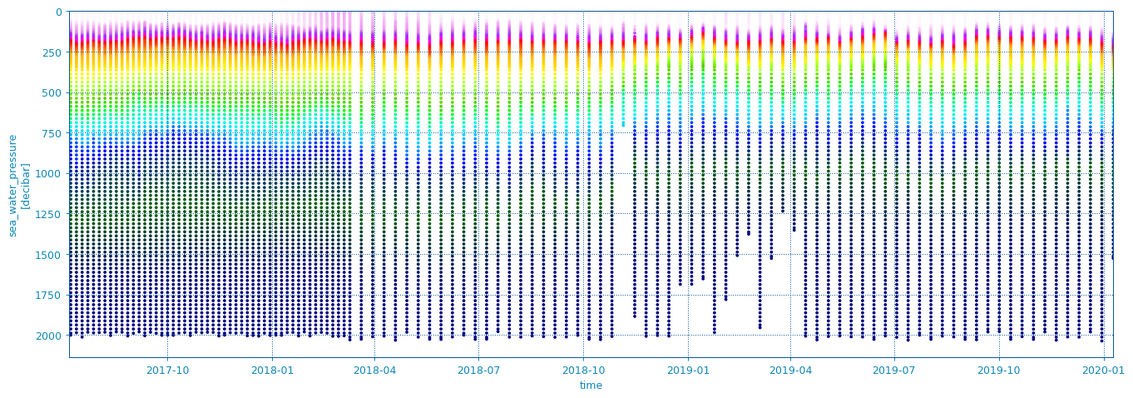

Plotting Temperature Across Multiple Profiles

Another useful feature of the Argopy library is that it can plot data

from multiple Argo profiles (dives). This can be done by supplying a

whole Xarray dataset for all our profiles; we can extract this from the

float_data object we got earlier by calling the

to_xarray() function on it. This can be passed to the

scatter_plot function in Argopy. We also have to give it

the variable name which is “TEMP” (or “PSAL” for salinity). This plot

uses colour to show the temperature and puts depth/pressure on the y

axis and date on the x axis.

Find Another Float to Plot

Pick a different float to load some data from. You can find a list of recently launched UK floats at https://fleetmonitoring.euro-argo.eu/dashboard?Status=Active&Year%20of%20deployment=2025&Country=United%20Kingdom&Network=CORE

Float numbers 7902230, 1902114, 1902725, 1902724, 1902109, 1902111, 1902110, 1902112, 4903834, 4903656, 6990513 or 2903943 could all be good contenders. Some floats will not work because they are missing data and you will ValueError, if this happens try a different float.

Create a new notebook with the following graphs for your float:

- A map showing where it has been

- A scatter plot of temperature against depth over time

- A scatter plot of salinity against depth over time

If you have time add some description about each graph by creating a cell with the Markdown type. Look at https://www.markdownguide.org/basic-syntax/ to see some of the syntax you can use with markdown.

- “Use the

pyplotmodule from thematplotliblibrary for creating simple visualisations.” - “Argopy has its own built in visaulisation functions”