Content from Automated Version Control

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 5 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is version control and why should I use it?

Objectives

- Understand the benefits of an automated version control system.

- Understand the basics of how automated version control systems work.

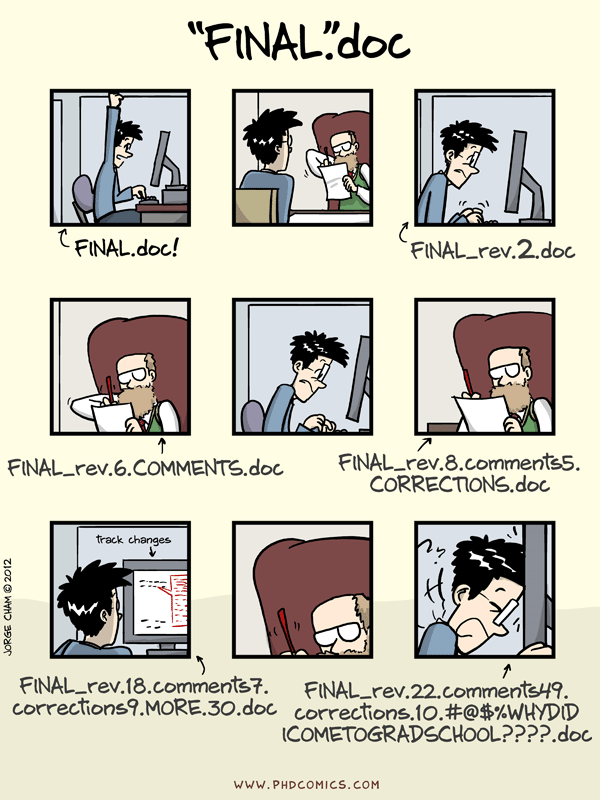

We’ll start by exploring how version control can be used to keep track of what one person did and when. Even if you aren’t collaborating with other people, automated version control is much better than this situation:

We’ve all been in this situation before: it seems unnecessary to have multiple nearly-identical versions of the same document. Some word processors let us deal with this a little better, such as Microsoft Word’s Track Changes, Google Docs’ version history, or LibreOffice’s Recording and Displaying Changes.

Version control systems start with a base version of the document and then record changes you make each step of the way. You can think of it as a recording of your progress: you can rewind to start at the base document and play back each change you made, eventually arriving at your more recent version.

Once you think of changes as separate from the document itself, you can then think about “playing back” different sets of changes on the base document, ultimately resulting in different versions of that document. For example, two users can make independent sets of changes on the same document.

Unless multiple users make changes to the same section of the document - a conflict - you can incorporate two sets of changes into the same base document.

A version control system is a tool that keeps track of these changes for us, effectively creating different versions of our files. It allows us to decide which changes will be made to the next version (each record of these changes is called a commit), and keeps useful metadata about them. The complete history of commits for a particular project and their metadata make up a repository. Repositories can be kept in sync across different computers, facilitating collaboration among different people.

The Long History of Version Control Systems

Automated version control systems are nothing new. Tools like RCS, CVS, or Subversion have been around since the early 1980s and are used by many large companies. However, many of these are now considered legacy systems (i.e., outdated) due to various limitations in their capabilities. More modern systems, such as Git and Mercurial, are distributed, meaning that they do not need a centralized server to host the repository. These modern systems also include powerful merging tools that make it possible for multiple authors to work on the same files concurrently.

Paper Writing

Imagine you drafted an excellent paragraph for a paper you are writing, but later ruin it. How would you retrieve the excellent version of your conclusion? Is it even possible?

Imagine you have 5 co-authors. How would you manage the changes and comments they make to your paper? If you use LibreOffice Writer or Microsoft Word, what happens if you accept changes made using the

Track Changesoption? Do you have a history of those changes?

Recovering the excellent version is only possible if you created a copy of the old version of the paper. The danger of losing good versions often leads to the problematic workflow illustrated in the PhD Comics cartoon at the top of this page.

Collaborative writing with traditional word processors is cumbersome. Either every collaborator has to work on a document sequentially (slowing down the process of writing), or you have to send out a version to all collaborators and manually merge their comments into your document. The ‘track changes’ or ‘record changes’ option can highlight changes for you and simplifies merging, but as soon as you accept changes you will lose their history. You will then no longer know who suggested that change, why it was suggested, or when it was merged into the rest of the document. Even online word processors like Google Docs or Microsoft Office Online do not fully resolve these problems.

Key Points

- Version control is like an unlimited ‘undo’.

- Version control also allows many people to work in parallel.

Content from Setting Up Git

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 5 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I get set up to use Git?

Objectives

- Configure

gitthe first time it is used on a computer. - Understand the meaning of the

--globalconfiguration flag.

When we use Git on a new computer for the first time, we need to configure a few things. Below are a few examples of configurations we will set as we get started with Git:

- our name and email address,

- what our preferred text editor is,

- and that we want to use these settings globally (i.e. for every project).

On a command line, Git commands are written as

git verb options, where verb is what we

actually want to do and options is additional optional

information which may be needed for the verb. So here is

how Alfredo sets up his new laptop:

BASH

$ git config --global user.name "Alfredo Linguini"

$ git config --global user.email "a.linguini@ratatouille.fr"Please use your own name and email address instead of Alfredo’s. This user name and email will be associated with your subsequent Git activity, which means that any changes pushed to GitHub, BitBucket, GitLab or another Git host server after this lesson will include this information.

For this lesson, we will be interacting with GitHub and so the email address used should be the same as the one used when setting up your GitHub account. If you are concerned about privacy, please review GitHub’s instructions for keeping your email address private.

Keeping your email private

If you elect to use a private email address with GitHub, then use

GitHub’s no-reply email address for the user.email value.

It looks like ID+username@users.noreply.github.com. You can

look up your own address in your GitHub email settings.

Line Endings

As with other keys, when you press Enter or ↵ or on Macs, Return on your keyboard, your computer encodes this input as a character. Different operating systems use different character(s) to represent the end of a line. (You may also hear these referred to as newlines or line breaks.) Because Git uses these characters to compare files, it may cause unexpected issues when editing a file on different machines. Though it is beyond the scope of this lesson, you can read more about this issue in the Pro Git book.

You can change the way Git recognizes and encodes line endings using

the core.autocrlf command to git config. The

following settings are recommended:

On macOS and Linux:

And on Windows:

Alfredo also has to set his favorite text editor, following this table:

| Editor | Configuration command |

|---|---|

| Atom | $ git config --global core.editor "atom --wait" |

| nano | $ git config --global core.editor "nano -w" |

| BBEdit (Mac, with command line tools) | $ git config --global core.editor "bbedit -w" |

| Sublime Text (Mac) | $ git config --global core.editor "/Applications/Sublime\ Text.app/Contents/SharedSupport/bin/subl -n -w" |

| Sublime Text (Win, 32-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files (x86)/sublime text 3/sublime_text.exe' -w" |

| Sublime Text (Win, 64-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files/sublime text 3/sublime_text.exe' -w" |

| Notepad (Win) | $ git config --global core.editor "c:/Windows/System32/notepad.exe" |

| Notepad++ (Win, 32-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files (x86)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe' -multiInst -notabbar -nosession -noPlugin" |

| Notepad++ (Win, 64-bit install) | $ git config --global core.editor "'c:/program files/Notepad++/notepad++.exe' -multiInst -notabbar -nosession -noPlugin" |

| Kate (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "kate" |

| Gedit (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "gedit --wait --new-window" |

| Scratch (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "scratch-text-editor" |

| Emacs | $ git config --global core.editor "emacs" |

| Vim | $ git config --global core.editor "vim" |

| VS Code | $ git config --global core.editor "code --wait" |

It is possible to reconfigure the text editor for Git whenever you want to change it.

Exiting Vim

Note that Vim is the default editor for many programs. If you haven’t

used Vim before and wish to exit a session without saving your changes,

press Esc then type :q! and press

Enter or ↵ or on Macs, Return. If you

want to save your changes and quit, press Esc then type

:wq and press Enter or ↵ or on Macs,

Return.

Git (2.28+) allows configuration of the name of the branch created

when you initialize any new repository. Alfredo decides to use that

feature to set it to main so it matches the cloud service

he will eventually use.

Default Git branch naming

Source file changes are associated with a “branch.” For new learners

in this lesson, it’s enough to know that branches exist, and this lesson

uses one branch.

By default, Git will create a branch called master when you

create a new repository with git init (as explained in the

next Episode). This term evokes the racist practice of human slavery and

the software development

community has moved to adopt more inclusive language.

In 2020, most Git code hosting services transitioned to using

main as the default branch. As an example, any new

repository that is opened in GitHub and GitLab default to

main. However, Git has not yet made the same change. As a

result, local repositories must be manually configured have the same

main branch name as most cloud services.

For versions of Git prior to 2.28, the change can be made on an

individual repository level. The command for this is in the next

episode. Note that if this value is unset in your local Git

configuration, the init.defaultBranch value defaults to

master.

The five commands we just ran above only need to be run once: the

flag --global tells Git to use the settings for every

project, in your user account, on this computer.

Let’s review those settings and test our core.editor

right away:

Let’s close the file without making any additional changes. Remember, since typos in the config file will cause issues, it’s safer to view the configuration with:

And if necessary, change your configuration using the same commands to choose another editor or update your email address. This can be done as many times as you want.

Proxy

In some networks you need to use a proxy. If this is the case, you may also need to tell Git about the proxy:

To disable the proxy, use

Git Help and Manual

Always remember that if you forget the subcommands or options of a

git command, you can access the relevant list of options

typing git <command> -h or access the corresponding

Git manual by typing git <command> --help, e.g.:

While viewing the manual, remember the : is a prompt

waiting for commands and you can press Q to exit the

manual.

More generally, you can get the list of available git

commands and further resources of the Git manual typing:

Key Points

- Use

git configwith the--globaloption to configure a user name, email address, editor, and other preferences once per machine.

Content from Creating a Repository

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 10 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Where does Git store information?

Objectives

- Create a local Git repository.

- Describe the purpose of the

.gitdirectory.

Once Git is configured, we can start using it.

We will help Alfredo with his new project, create a repository with all his recipes.

First, let’s create a new directory in the Desktop

folder for our work and then change the current working directory to the

newly created one:

Then we tell Git to make recipes a repository -- a place where Git can

store versions of our files:

It is important to note that git init will create a

repository that can include subdirectories and their files—there is no

need to create separate repositories nested within the

recipes repository, whether subdirectories are present from

the beginning or added later. Also, note that the creation of the

recipes directory and its initialization as a repository

are completely separate processes.

If we use ls to show the directory’s contents, it

appears that nothing has changed:

But if we add the -a flag to show everything, we can see

that Git has created a hidden directory within recipes

called .git:

OUTPUT

. .. .gitGit uses this special subdirectory to store all the information about

the project, including the tracked files and sub-directories located

within the project’s directory. If we ever delete the .git

subdirectory, we will lose the project’s history.

We can now start using one of the most important git commands, which

is particularly helpful to beginners. git status tells us

the status of our project, and better, a list of changes in the project

and options on what to do with those changes. We can use it as often as

we want, whenever we want to understand what is going on.

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)If you are using a different version of git, the exact

wording of the output might be slightly different.

Places to Create Git Repositories

Along with tracking information about recipes (the project we have

already created), Alfredo would also like to track information about

desserts specifically. Alfredo creates a desserts project

inside his recipes project with the following sequence of

commands:

BASH

$ cd ~/Desktop # return to Desktop directory

$ cd recipes # go into recipes directory, which is already a Git repository

$ ls -a # ensure the .git subdirectory is still present in the recipes directory

$ mkdir desserts # make a sub-directory recipes/desserts

$ cd desserts # go into desserts subdirectory

$ git init # make the desserts subdirectory a Git repository

$ ls -a # ensure the .git subdirectory is present indicating we have created a new Git repositoryIs the git init command, run inside the

desserts subdirectory, required for tracking files stored

in the desserts subdirectory?

No. Alfredo does not need to make the desserts

subdirectory a Git repository because the recipes

repository will track all files, sub-directories, and subdirectory files

under the recipes directory. Thus, in order to track all

information about desserts, Alfredo only needed to add the

desserts subdirectory to the recipes

directory.

Additionally, Git repositories can interfere with each other if they

are “nested”: the outer repository will try to version-control the inner

repository. Therefore, it’s best to create each new Git repository in a

separate directory. To be sure that there is no conflicting repository

in the directory, check the output of git status. If it

looks like the following, you are good to go to create a new repository

as shown above:

OUTPUT

fatal: Not a git repository (or any of the parent directories): .gitCorrecting git init Mistakes

Jimmy explains to Alfredo how a nested repository is redundant and

may cause confusion down the road. Alfredo would like to go back to a

single git repository. How can Alfredo undo his last

git init in the desserts subdirectory?

Background

Removing files from a Git repository needs to be done with caution. But we have not learned yet how to tell Git to track a particular file; we will learn this in the next episode. Files that are not tracked by Git can easily be removed like any other “ordinary” files with

Similarly a directory can be removed using

rm -r dirname. If the files or folder being removed in this

fashion are tracked by Git, then their removal becomes another change

that we will need to track, as we will see in the next episode.

Solution

Git keeps all of its files in the .git directory. To

recover from this little mistake, Alfredo can remove the

.git folder in the desserts subdirectory by running the

following command from inside the recipes directory:

But be careful! Running this command in the wrong directory will

remove the entire Git history of a project you might want to keep. In

general, deleting files and directories using rm from the

command line cannot be reversed. Therefore, always check your current

directory using the command pwd.

Key Points

-

git initinitializes a repository. - Git stores all of its repository data in the

.gitdirectory.

Content from Tracking Changes

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I record changes in Git?

- How do I check the status of my version control repository?

- How do I record notes about what changes I made and why?

Objectives

- Go through the modify-add-commit cycle for one or more files.

- Explain where information is stored at each stage of that cycle.

- Distinguish between descriptive and non-descriptive commit messages.

First let’s make sure we’re still in the right directory. You should

be in the recipes directory.

Let’s create a file called guacamole.md that contains

the basic structure to have a recipe. We’ll use nano to

edit the file; you can use whatever editor you like. In particular, this

does not have to be the core.editor you set globally

earlier. But remember, the steps to create create or edit a new file

will depend on the editor you choose (it might not be nano). For a

refresher on text editors, check out “Which

Editor?” in The Unix Shell

lesson.

Type the text below into the guacamole.md file:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

## InstructionsSave the file and exit your editor. Next, let’s verify that the file

was properly created by running the list command (ls):

OUTPUT

guacamole.mdguacamole.md contains three lines, which we can see by

running:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

## InstructionsIf we check the status of our project again, Git tells us that it’s noticed the new file:

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

guacamole.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The “untracked files” message means that there’s a file in the

directory that Git isn’t keeping track of. We can tell Git to track a

file using git add:

and then check that the right thing happened:

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: guacamole.md

Git now knows that it’s supposed to keep track of

guacamole.md, but it hasn’t recorded these changes as a

commit yet. To get it to do that, we need to run one more command:

OUTPUT

[main (root-commit) f22b25e] Create a template for recipe

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 guacamole.mdWhen we run git commit, Git takes everything we have

told it to save by using git add and stores a copy

permanently inside the special .git directory. This

permanent copy is called a commit

(or revision) and its short

identifier is f22b25e. Your commit may have another

identifier.

We use the -m flag (for “message”) to record a short,

descriptive, and specific comment that will help us remember later on

what we did and why. If we just run git commit without the

-m option, Git will launch nano (or whatever

other editor we configured as core.editor) so that we can

write a longer message.

Good commit

messages start with a brief (<50 characters) statement about the

changes made in the commit. Generally, the message should complete the

sentence “If applied, this commit will”

If we run git status now:

OUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanit tells us everything is up to date. If we want to know what we’ve

done recently, we can ask Git to show us the project’s history using

git log:

OUTPUT

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Create a template for recipegit log lists all commits made to a repository in

reverse chronological order. The listing for each commit includes the

commit’s full identifier (which starts with the same characters as the

short identifier printed by the git commit command

earlier), the commit’s author, when it was created, and the log message

Git was given when the commit was created.

Where Are My Changes?

If we run ls at this point, we will still see just one

file called guacamole.md. That’s because Git saves

information about files’ history in the special .git

directory mentioned earlier so that our filesystem doesn’t become

cluttered (and so that we can’t accidentally edit or delete an old

version).

Now suppose Alfredo adds more information to the file. (Again, we’ll

edit with nano and then cat the file to show

its contents; you may use a different editor, and don’t need to

cat.)

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lemon

* salt

## InstructionsWhen we run git status now, it tells us that a file it

already knows about has been modified:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")The last line is the key phrase: “no changes added to commit”. We

have changed this file, but we haven’t told Git we will want to save

those changes (which we do with git add) nor have we saved

them (which we do with git commit). So let’s do that now.

It is good practice to always review our changes before saving them. We

do this using git diff. This shows us the differences

between the current state of the file and the most recently saved

version:

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index df0654a..315bf3a 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,3 +1,6 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

+* avocado

+* lemon

+* salt

## InstructionsThe output is cryptic because it is actually a series of commands for

tools like editors and patch telling them how to

reconstruct one file given the other. If we break it down into

pieces:

- The first line tells us that Git is producing output similar to the

Unix

diffcommand comparing the old and new versions of the file. - The second line tells exactly which versions of the file Git is

comparing;

df0654aand315bf3aare unique computer-generated labels for those versions. - The third and fourth lines once again show the name of the file being changed.

- The remaining lines are the most interesting, they show us the

actual differences and the lines on which they occur. In particular, the

+marker in the first column shows where we added a line.

After reviewing our change, it’s time to commit it:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Whoops: Git won’t commit because we didn’t use git add

first. Let’s fix that:

OUTPUT

[main 34961b1] Add basic guacamole's ingredient

1 file changed, 3 insertions(+)Git insists that we add files to the set we want to commit before actually committing anything. This allows us to commit our changes in stages and capture changes in logical portions rather than only large batches. For example, suppose we’re adding a few citations to relevant research to our thesis. We might want to commit those additions, and the corresponding bibliography entries, but not commit some of our work drafting the conclusion (which we haven’t finished yet).

To allow for this, Git has a special staging area where it keeps track of things that have been added to the current changeset but not yet committed.

Staging Area

If you think of Git as taking snapshots of changes over the life of a

project, git add specifies what will go in a

snapshot (putting things in the staging area), and

git commit then actually takes the snapshot, and

makes a permanent record of it (as a commit). If you don’t have anything

staged when you type git commit, Git will prompt you to use

git commit -a or git commit --all, which is

kind of like gathering everyone to take a group photo! However,

it’s almost always better to explicitly add things to the staging area,

because you might commit changes you forgot you made. (Going back to the

group photo simile, you might get an extra with incomplete makeup

walking on the stage for the picture because you used -a!)

Try to stage things manually, or you might find yourself searching for

“git undo commit” more than you would like!

Let’s watch as our changes to a file move from our editor to the staging area and into long-term storage. First, we’ll improve our recipe by changing ‘lemon’ to ‘lime’:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## InstructionsOUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

-* lemon

+* lime

* salt

## InstructionsSo far, so good: we’ve replaced one line (shown with a -

in the first column) with a new line (shown with a + in the

first column). Now let’s put that change in the staging area and see

what git diff reports:

There is no output: as far as Git can tell, there’s no difference between what it’s been asked to save permanently and what’s currently in the directory. However, if we do this:

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

-* lemon

+* lime

* salt

## Instructionsit shows us the difference between the last committed change and what’s in the staging area. Let’s save our changes:

OUTPUT

[main 005937f] Modify guacamole to the traditional recipe

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)check our status:

OUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanand look at the history of what we’ve done so far:

OUTPUT

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Modify guacamole to the traditional recipe

commit 34961b159c27df3b475cfe4415d94a6d1fcd064d

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Add basic guacamole's ingredients

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Create a template for recipeWord-based diffing

Sometimes, e.g. in the case of the text documents a line-wise diff is

too coarse. That is where the --color-words option of

git diff comes in very useful as it highlights the changed

words using colors.

Paging the Log

When the output of git log is too long to fit in your

screen, git uses a program to split it into pages of the

size of your screen. When this “pager” is called, you will notice that

the last line in your screen is a :, instead of your usual

prompt.

- To get out of the pager, press Q.

- To move to the next page, press Spacebar.

- To search for

some_wordin all pages, press / and typesome_word. Navigate through matches pressing N.

Limit Log Size

To avoid having git log cover your entire terminal

screen, you can limit the number of commits that Git lists by using

-N, where N is the number of commits that you

want to view. For example, if you only want information from the last

commit you can use:

OUTPUT

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Modify guacamole to the traditional recipeYou can also reduce the quantity of information using the

--oneline option:

OUTPUT

005937f (HEAD -> main) Modify guacamole to the traditional recipe

34961b1 Add basic guacamole's ingredients

f22b25e Create a template for recipeYou can also combine the --oneline option with others.

One useful combination adds --graph to display the commit

history as a text-based graph and to indicate which commits are

associated with the current HEAD, the current branch

main, or other

Git references:

OUTPUT

* 005937f (HEAD -> main) Modify guacamole to the traditional recipe

* 34961b1 Add basic guacamole's ingredients

* f22b25e Create a template for recipeDirectories

Two important facts you should know about directories in Git.

- Git does not track directories on their own, only files within them. Try it for yourself:

Note, our newly created empty directory cakes does not

appear in the list of untracked files even if we explicitly add it

(via git add) to our repository. This is the

reason why you will sometimes see .gitkeep files in

otherwise empty directories. Unlike .gitignore, these files

are not special and their sole purpose is to populate a directory so

that Git adds it to the repository. In fact, you can name such files

anything you like.

- If you create a directory in your Git repository and populate it with files, you can add all files in the directory at once by:

Try it for yourself:

Before moving on, we will commit these changes.

To recap, when we want to add changes to our repository, we first

need to add the changed files to the staging area (git add)

and then commit the staged changes to the repository

(git commit):

Choosing a Commit Message

Which of the following commit messages would be most appropriate for

the last commit made to guacamole.md?

- “Changes”

- “Changed lemon for lime”

- “Guacamole modified to the traditional recipe”

Answer 1 is not descriptive enough, and the purpose of the commit is unclear; and answer 2 is redundant to using “git diff” to see what changed in this commit; but answer 3 is good: short, descriptive, and imperative.

Committing Changes to Git

Which command(s) below would save the changes of

myfile.txt to my local Git repository?

- Would only create a commit if files have already been staged.

- Would try to create a new repository.

- Is correct: first add the file to the staging area, then commit.

- Would try to commit a file “my recent changes” with the message myfile.txt.

Committing Multiple Files

The staging area can hold changes from any number of files that you want to commit as a single snapshot.

- Add some text to

guacamole.mdnoting the rough price of the ingredients. - Create a new file

groceries.mdwith a list of products and their prices for different markets. - Add changes from both files to the staging area, and commit those changes.

First we make our changes to the guacamole.md and

groceries.md files:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado (1.35)

* lime (0.64)

* salt (2)OUTPUT

# Market A

* avocado: 1.35 per unit.

* lime: 0.64 per unit

* salt: 2 per kgNow you can add both files to the staging area. We can do that in one line:

Or with multiple commands:

Now the files are ready to commit. You can check that using

git status. If you are ready to commit use:

OUTPUT

[main cc127c2]

Write prices for ingredients and their source

2 files changed, 7 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 groceries.md

bio Repository

- Create a new Git repository on your computer called

bio. - Write a three-line biography for yourself in a file called

me.txt, commit your changes - Modify one line, add a fourth line

- Display the differences between its updated state and its original state.

If needed, move out of the recipes folder:

Create a new folder called bio and ‘move’ into it:

Initialise git:

Create your biography file me.txt using

nano or another text editor. Once in place, add and commit

it to the repository:

Modify the file as described (modify one line, add a fourth line). To

display the differences between its updated state and its original

state, use git diff:

Key Points

-

git statusshows the status of a repository. - Files can be stored in a project’s working directory (which users see), the staging area (where the next commit is being built up) and the local repository (where commits are permanently recorded).

-

git addputs files in the staging area. -

git commitsaves the staged content as a new commit in the local repository. - Write a commit message that accurately describes your changes.

Content from Exploring History

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I identify old versions of files?

- How do I review my changes?

- How can I recover old versions of files?

Objectives

- Explain what the HEAD of a repository is and how to use it.

- Identify and use Git commit numbers.

- Compare various versions of tracked files.

- Restore old versions of files.

As we saw in the previous episode, we can refer to commits by their

identifiers. You can refer to the most recent commit of the

working directory by using the identifier HEAD.

We’ve been adding small changes at a time to

guacamole.md, so it’s easy to track our progress by

looking, so let’s do that using our HEADs. Before we start,

let’s make a change to guacamole.md, adding yet another

line.

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

An ill-considered changeNow, let’s see what we get.

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index b36abfd..0848c8d 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -4,3 +4,4 @@

* lime

* salt

## Instructions

+An ill-considered changewhich is the same as what you would get if you leave out

HEAD (try it). The real goodness in all this is when you

can refer to previous commits. We do that by adding ~1

(where “~” is “tilde”, pronounced [til-duh])

to refer to the commit one before HEAD.

If we want to see the differences between older commits we can use

git diff again, but with the notation HEAD~1,

HEAD~2, and so on, to refer to them:

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index df0654a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,3 +1,6 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

+* avocado

+* lime

+* salt

## InstructionsWe could also use git show which shows us what changes

we made at an older commit as well as the commit message, rather than

the differences between a commit and our working directory that

we see by using git diff.

OUTPUT

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Alfredo Linguini <a.linguini@ratatouille.fr>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Create a template for recipe

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..df0654a

--- /dev/null

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -0,0 +1,3 @@

+# Guacamole

+## Ingredients

+## InstructionsIn this way, we can build up a chain of commits. The most recent end

of the chain is referred to as HEAD; we can refer to

previous commits using the ~ notation, so

HEAD~1 means “the previous commit”, while

HEAD~123 goes back 123 commits from where we are now.

We can also refer to commits using those long strings of digits and

letters that both git log and git show

display. These are unique IDs for the changes, and “unique” really does

mean unique: every change to any set of files on any computer has a

unique 40-character identifier. Our first commit was given the ID

f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b, so let’s try

this:

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index df0654a..93a3e13 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,3 +1,7 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

+* avocado

+* lime

+* salt

## Instructions

+An ill-considered changeThat’s the right answer, but typing out random 40-character strings is annoying, so Git lets us use just the first few characters (typically seven for normal size projects):

OUTPUT

diff --git a/guacamole.md b/guacamole.md

index df0654a..93a3e13 100644

--- a/guacamole.md

+++ b/guacamole.md

@@ -1,3 +1,7 @@

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

+* avocado

+* lime

+* salt

## Instructions

+An ill-considered changeAll right! So we can save changes to files and see what we’ve

changed. Now, how can we restore older versions of things? Let’s suppose

we change our mind about the last update to guacamole.md

(the “ill-considered change”).

git status now tells us that the file has been changed,

but those changes haven’t been staged:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")We can put things back the way they were by using

git restore:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## InstructionsAs you might guess from its name, git restore restores

an old version of a file. By default, it recovers the version of the

file recorded in HEAD, which is the last saved commit. If

we want to go back even further, we can use a commit identifier instead,

using -s option:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

## InstructionsOUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Notice that the changes are not currently in the staging area, and

have not been committed. If we wished, we can put things back the way

they were at the last commit by using git restore to

overwrite the working copy with the last committed version:

OUTPUT

# Guacamole

## Ingredients

* avocado

* lime

* salt

## InstructionsIt’s important to remember that we must use the commit number that

identifies the state of the repository before the change we’re

trying to undo. A common mistake is to use the number of the commit in

which we made the change we’re trying to discard. In the example below,

we want to retrieve the state from before the most recent commit

(HEAD~1), which is commit f22b25e. We use the

. to mean all files:

So, to put it all together, here’s how Git works in cartoon form:

The fact that files can be reverted one by one tends to change the way people organize their work. If everything is in one large document, it’s hard (but not impossible) to undo changes to the introduction without also undoing changes made later to the conclusion. If the introduction and conclusion are stored in separate files, on the other hand, moving backward and forward in time becomes much easier.

Recovering Older Versions of a File

Jennifer has made changes to the Python script that she has been working on for weeks, and the modifications she made this morning “broke” the script and it no longer runs. She has spent ~ 1hr trying to fix it, with no luck…

Luckily, she has been keeping track of her project’s versions using

Git! Which commands below will let her recover the last committed

version of her Python script called data_cruncher.py?

$ git restore$ git restore data_cruncher.py$ git restore -s HEAD~1 data_cruncher.py$ git restore -s <unique ID of last commit> data_cruncher.pyBoth 2 and 4

The answer is (5)-Both 2 and 4.

The restore command restores files from the repository,

overwriting the files in your working directory. Answers 2 and 4 both

restore the latest version in the repository of the

file data_cruncher.py. Answer 2 uses HEAD to

indicate the latest, whereas answer 4 uses the unique ID of the

last commit, which is what HEAD means.

Answer 3 gets the version of data_cruncher.py from the

commit before HEAD, which is NOT what we

wanted.

Answer 1 results in an error. You need to specify a file to restore.

If you want to restore all files you should use

git restore .

Reverting a Commit

Jennifer is collaborating with colleagues on her Python script. She

realizes her last commit to the project’s repository contained an error,

and wants to undo it. Jennifer wants to undo correctly so everyone in

the project’s repository gets the correct change. The command

git revert [erroneous commit ID] will create a new commit

that reverses the erroneous commit.

The command git revert is different from

git restore -s [commit ID] . because

git restore returns the files not yet committed within the

local repository to a previous state, whereas git revert

reverses changes committed to the local and project repositories.

Below are the right steps and explanations for Jennifer to use

git revert, what is the missing command?

________ # Look at the git history of the project to find the commit IDCopy the ID (the first few characters of the ID, e.g. 0b1d055).

git revert [commit ID]Type in the new commit message.

Save and close.

The command git log lists project history with commit

IDs.

The command git show HEAD shows changes made at the

latest commit, and lists the commit ID; however, Jennifer should

double-check it is the correct commit, and no one else has committed

changes to the repository.

Understanding Workflow and History

What is the output of the last command in

BASH

$ cd recipes

$ echo "I like tomatoes, therefore I like ketchup" > ketchup.md

$ git add ketchup.md

$ echo "ketchup enhances pasta dishes" >> ketchup.md

$ git commit -m "My opinions about the red sauce"

$ git restore ketchup.md

$ cat ketchup.md # this will print the content of ketchup.md on screenOUTPUT

ketchup enhances pasta dishesOUTPUT

I like tomatoes, therefore I like ketchupOUTPUT

I like tomatoes, therefore I like ketchup ketchup enhances pasta dishesOUTPUT

Error because you have changed ketchup.md without committing the changes

The answer is 2.

The changes to the file from the second echo command are

only applied to the working copy, not the version in the staging area.

The command git add ketchup.md places the current version

of ketchup.md into the staging area.

So, when git commit -m "My opinions about the red sauce"

is executed, the version of ketchup.md committed to the

repository is the one from the staging area and has only one line.

At this time, the working copy still has the second line (and

git status will show that the file is modified).

However, git restore ketchup.md replaces the working copy

with the most recently committed version of ketchup.md. So,

cat ketchup.md will output

OUTPUT

I like tomatoes, therefore I like ketchupChecking Understanding of

git diff

Consider this command: git diff HEAD~9 guacamole.md.

What do you predict this command will do if you execute it? What happens

when you do execute it? Why?

Try another command, git diff [ID] guacamole.md, where

[ID] is replaced with the unique identifier for your most recent commit.

What do you think will happen, and what does happen?

Getting Rid of Staged Changes

git restore can be used to restore a previous commit

when unstaged changes have been made, but will it also work for changes

that have been staged but not committed? Make a change to

guacamole.md, add that change using git add,

then use git restore to see if you can remove your

change.

After adding a change, git restore can not be used

directly. Let’s look at the output of git status:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: guacamole.md

Note that if you don’t have the same output you may either have forgotten to change the file, or you have added it and committed it.

Using the command git restore guacamole.md now does not

give an error, but it does not restore the file either. Git helpfully

tells us that we need to use git restore --staged first to

unstage the file:

Now, git status gives us:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: guacamole.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")This means we can now use git restore to restore the

file to the previous commit:

OUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanExplore and Summarize Histories

Exploring history is an important part of Git, and often it is a challenge to find the right commit ID, especially if the commit is from several months ago.

Imagine the recipes project has more than 50 files. You

would like to find a commit that modifies some specific text in

guacamole.md. When you type git log, a very

long list appeared. How can you narrow down the search?

Recall that the git diff command allows us to explore

one specific file, e.g., git diff guacamole.md. We can

apply a similar idea here.

Unfortunately some of these commit messages are very ambiguous, e.g.,

update files. How can you search through these files?

Both git diff and git log are very useful

and they summarize a different part of the history for you. Is it

possible to combine both? Let’s try the following:

You should get a long list of output, and you should be able to see both commit messages and the difference between each commit.

Question: What does the following command do?

Key Points

-

git diffdisplays differences between commits. -

git restorerecovers old versions of files.

Content from Ignoring Things

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 5 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I tell Git to ignore files I don’t want to track?

Objectives

- Configure Git to ignore specific files.

- Explain why ignoring files can be useful.

What if we have files that we do not want Git to track for us, like backup files created by our editor or intermediate files created during data analysis? Let’s create a few dummy files:

and see what Git says:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

a.png

b.png

c.png

receipts/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Putting these files under version control would be a waste of disk space. What’s worse, having them all listed could distract us from changes that actually matter, so let’s tell Git to ignore them.

We do this by creating a file in the root directory of our project

called .gitignore:

OUTPUT

*.png

receipts/These patterns tell Git to ignore any file whose name ends in

.png and everything in the receipts directory.

(If any of these files were already being tracked, Git would continue to

track them.)

Once we have created this file, the output of git status

is much cleaner:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.gitignore

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The only thing Git notices now is the newly-created

.gitignore file. You might think we wouldn’t want to track

it, but everyone we’re sharing our repository with will probably want to

ignore the same things that we’re ignoring. Let’s add and commit

.gitignore:

OUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanAs a bonus, using .gitignore helps us avoid accidentally

adding files to the repository that we don’t want to track:

OUTPUT

The following paths are ignored by one of your .gitignore files:

a.png

Use -f if you really want to add them.If we really want to override our ignore settings, we can use

git add -f to force Git to add something. For example,

git add -f a.csv. We can also always see the status of

ignored files if we want:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Ignored files:

(use "git add -f <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

a.png

b.png

c.png

receipts/

nothing to commit, working tree cleanIf you only want to ignore the contents of

receipts/plots, you can change your .gitignore

to ignore only the /plots/ subfolder by adding the

following line to your .gitignore:

OUTPUT

receipts/plots/This line will ensure only the contents of

receipts/plots is ignored, and not the contents of

receipts/data.

As with most programming issues, there are a few alternative ways that one may ensure this ignore rule is followed. The “Ignoring Nested Files: Variation” exercise has a slightly different directory structure that presents an alternative solution. Further, the discussion page has more detail on ignore rules.

Including Specific Files

How would you ignore all .png files in your root

directory except for final.png? Hint: Find out what

! (the exclamation point operator) does

You would add the following two lines to your .gitignore:

OUTPUT

*.png # ignore all png files

!final.png # except final.pngThe exclamation point operator will include a previously excluded entry.

Note also that because you’ve previously committed .png

files in this lesson they will not be ignored with this new rule. Only

future additions of .png files added to the root directory

will be ignored.

Ignoring Nested Files: Variation

Given a directory structure that looks similar to the earlier Nested Files exercise, but with a slightly different directory structure:

How would you ignore all of the contents in the receipts folder, but

not receipts/data?

Hint: think a bit about how you created an exception with the

! operator before.

If you want to ignore the contents of receipts/ but not

those of receipts/data/, you can change your

.gitignore to ignore the contents of receipts folder, but

create an exception for the contents of the receipts/data

subfolder. Your .gitignore would look like this:

OUTPUT

receipts/* # ignore everything in receipts folder

!receipts/data/ # do not ignore receipts/data/ contentsIgnoring all data Files in a Directory

Assuming you have an empty .gitignore file, and given a directory structure that looks like:

BASH

receipts/data/market_position/gps/a.dat

receipts/data/market_position/gps/b.dat

receipts/data/market_position/gps/c.dat

receipts/data/market_position/gps/info.txt

receipts/plotsWhat’s the shortest .gitignore rule you could write to

ignore all .dat files in

result/data/market_position/gps? Do not ignore the

info.txt.

Appending receipts/data/market_position/gps/*.dat will

match every file in receipts/data/market_position/gps that

ends with .dat. The file

receipts/data/market_position/gps/info.txt will not be

ignored.

Ignoring all data Files in the repository

Let us assume you have many .csv files in different

subdirectories of your repository. For example, you might have:

BASH

results/a.csv

data/experiment_1/b.csv

data/experiment_2/c.csv

data/experiment_2/variation_1/d.csvHow do you ignore all the .csv files, without explicitly

listing the names of the corresponding folders?

In the .gitignore file, write:

OUTPUT

**/*.csvThis will ignore all the .csv files, regardless of their

position in the directory tree. You can still include some specific

exception with the exclamation point operator.

The ! modifier will negate an entry from a previously

defined ignore pattern. Because the !*.csv entry negates

all of the previous .csv files in the

.gitignore, none of them will be ignored, and all

.csv files will be tracked.

Log Files

You wrote a script that creates many intermediate log-files of the

form log_01, log_02, log_03, etc.

You want to keep them but you do not want to track them through

git.

Write one

.gitignoreentry that excludes files of the formlog_01,log_02, etc.Test your “ignore pattern” by creating some dummy files of the form

log_01, etc.You find that the file

log_01is very important after all, add it to the tracked files without changing the.gitignoreagain.Discuss with your neighbor what other types of files could reside in your directory that you do not want to track and thus would exclude via

.gitignore.

- append either

log_*orlog*as a new entry in your .gitignore - track

log_01usinggit add -f log_01

Key Points

- The .gitignore file is a text file that tells Git which files to track and which to ignore in the repository.

- You can list specific files or folders to be ignored by Git, or you can include files that would normally be ignored.

Content from Remotes in GitHub

Last updated on 2024-12-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I share my changes with others on the web?

Objectives

- Explain what remote repositories are and why they are useful.

- Push to or pull from a remote repository.

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people. We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

Systems like Git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop. Most programmers use hosting services like GitHub, Bitbucket or GitLab to hold those main copies; we’ll explore the pros and cons of this in a later episode.

Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project with the world. To this end we are going to create a remote repository that will be linked to our local repository.

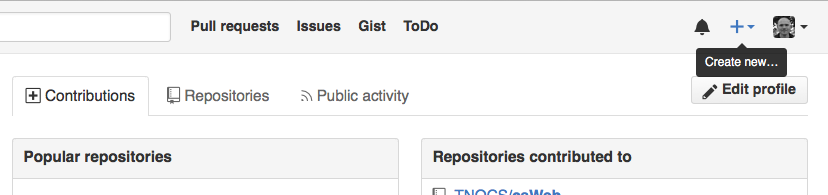

1. Create a remote repository

Log in to GitHub, then click on the

icon in the top right corner to create a new repository called

recipes:

Name your repository “recipes” and then click “Create Repository”.

Note: Since this repository will be connected to a local repository, it needs to be empty. Leave “Initialize this repository with a README” unchecked, and keep “None” as options for both “Add .gitignore” and “Add a license.” See the “GitHub License and README files” exercise below for a full explanation of why the repository needs to be empty.

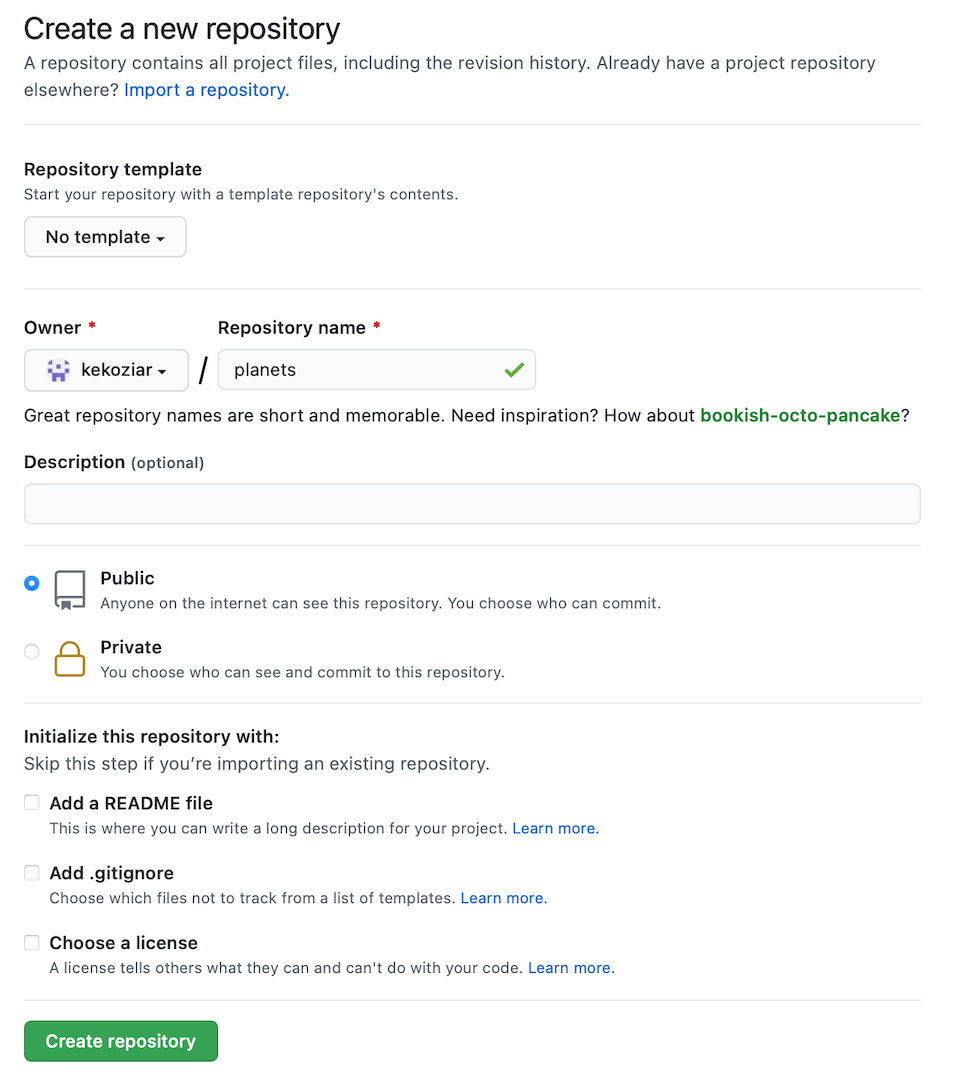

As soon as the repository is created, GitHub displays a page with a URL and some information on how to configure your local repository:

This effectively does the following on GitHub’s servers:

If you remember back to the earlier episode where we added and committed our

earlier work on guacamole.md, we had a diagram of the local

repository which looked like this:

Now that we have two repositories, we need a diagram like this:

Note that our local repository still contains our earlier work on

guacamole.md, but the remote repository on GitHub appears

empty as it doesn’t contain any files yet.

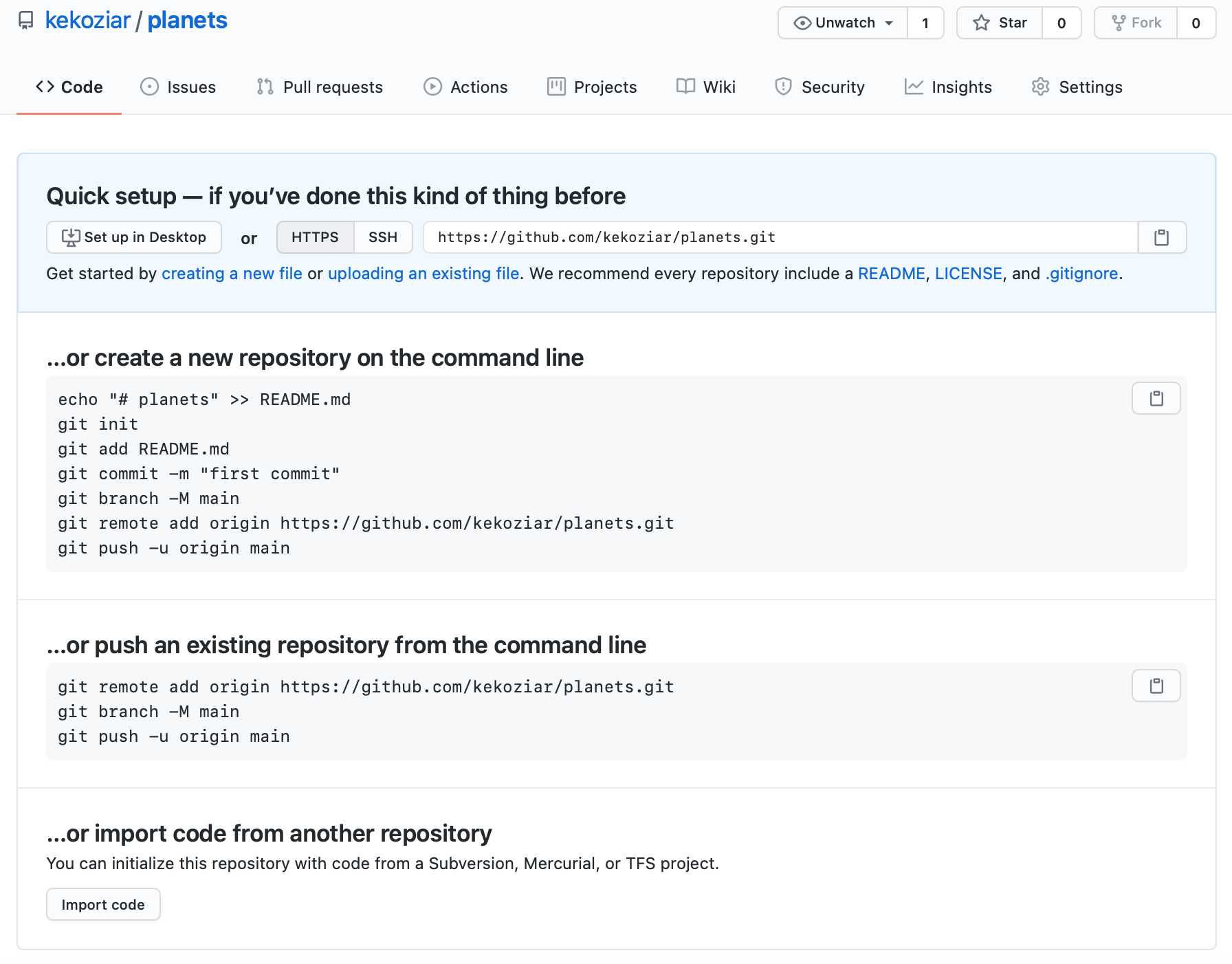

2. Connect local to remote repository

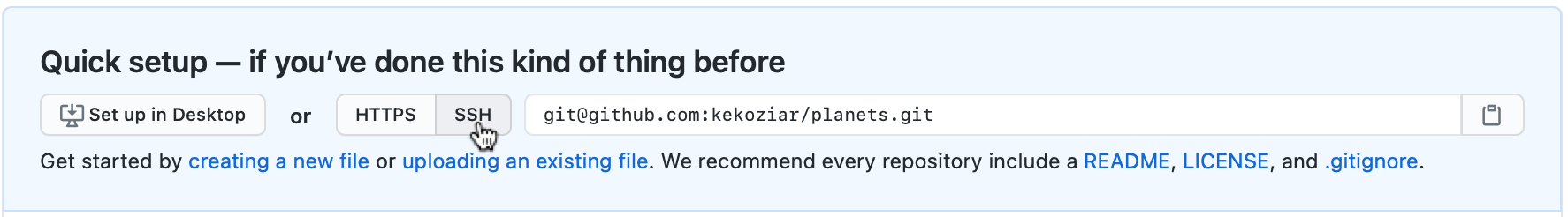

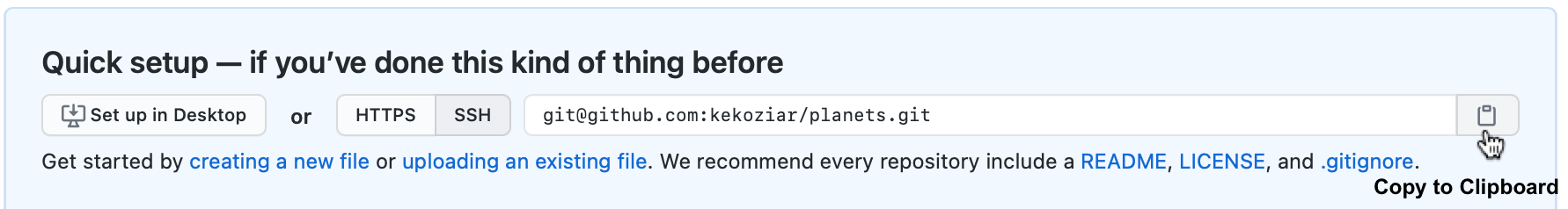

Now we connect the two repositories. We do this by making the GitHub repository a remote for the local repository. The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the URL string we need to identify it:

Click on the ‘SSH’ link to change the protocol from HTTPS to SSH.

HTTPS vs. SSH

We use SSH here because, while it requires some additional configuration, it is a security protocol widely used by many applications. The steps below describe SSH at a minimum level for GitHub.

Copy that URL from the browser, go into the local

recipes repository, and run this command:

Make sure to use the URL for your repository rather than Alfredo’s:

the only difference should be your username instead of

alflin.

origin is a local name used to refer to the remote

repository. It could be called anything, but origin is a

convention that is often used by default in git and GitHub, so it’s

helpful to stick with this unless there’s a reason not to.

We can check that the command has worked by running

git remote -v:

OUTPUT

origin git@github.com:alflin/recipes.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:alflin/recipes.git (push)We’ll discuss remotes in more detail in the next episode, while talking about how they might be used for collaboration.

3. SSH Background and Setup

Before Alfredo can connect to a remote repository, he needs to set up a way for his computer to authenticate with GitHub so it knows it’s him trying to connect to his remote repository.

We are going to set up the method that is commonly used by many different services to authenticate access on the command line. This method is called Secure Shell Protocol (SSH). SSH is a cryptographic network protocol that allows secure communication between computers using an otherwise insecure network.

SSH uses what is called a key pair. This is two keys that work together to validate access. One key is publicly known and called the public key, and the other key called the private key is kept private. Very descriptive names.

You can think of the public key as a padlock, and only you have the key (the private key) to open it. You use the public key where you want a secure method of communication, such as your GitHub account. You give this padlock, or public key, to GitHub and say “lock the communications to my account with this so that only computers that have my private key can unlock communications and send git commands as my GitHub account.”

What we will do now is the minimum required to set up the SSH keys and add the public key to a GitHub account.

Advanced SSH

A supplemental episode in this lesson discusses SSH and key pairs in more depth and detail.

The first thing we are going to do is check if this has already been done on the computer you’re on. Because generally speaking, this setup only needs to happen once and then you can forget about it.

Keeping your keys secure

You shouldn’t really forget about your SSH keys, since they keep your account secure. It’s good practice to audit your secure shell keys every so often. Especially if you are using multiple computers to access your account.

We will run the list command to check what key pairs already exist on your computer.

Your output is going to look a little different depending on whether or not SSH has ever been set up on the computer you are using.

Alfredo has not set up SSH on his computer, so his output is

OUTPUT

ls: cannot access '/c/Users/Alfredo/.ssh': No such file or directoryIf SSH has been set up on the computer you’re using, the public and

private key pairs will be listed. The file names are either

id_ed25519/id_ed25519.pub or

id_rsa/id_rsa.pub depending on how the key

pairs were set up. Since they don’t exist on Alfredo’s computer, he uses

this command to create them.

3.1 Create an SSH key pair

To create an SSH key pair Alfredo uses this command, where the

-t option specifies which type of algorithm to use and

-C attaches a comment to the key (here, Alfredo’s

email):

If you are using a legacy system that doesn’t support the Ed25519

algorithm, use:

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "your_email@example.com"

OUTPUT

Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/c/Users/Alfredo/.ssh/id_ed25519):We want to use the default file, so just press Enter.

OUTPUT

Created directory '/c/Users/Alfredo/.ssh'.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):Now, it is prompting Alfredo for a passphrase. Since he is using his kitchen’s laptop that other people sometimes have access to, he wants to create a passphrase. Be sure to use something memorable or save your passphrase somewhere, as there is no “reset my password” option. Note that, when typing a passphrase on a terminal, there won’t be any visual feedback of your typing. This is normal: your passphrase will be recorded even if you see nothing changing on your screen.

OUTPUT

Enter same passphrase again:After entering the same passphrase a second time, we receive the confirmation

OUTPUT

Your identification has been saved in /c/Users/Alfredo/.ssh/id_ed25519

Your public key has been saved in /c/Users/Alfredo/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:SMSPIStNyA00KPxuYu94KpZgRAYjgt9g4BA4kFy3g1o a.linguini@ratatouille.fr

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ED25519 256]--+

|^B== o. |

|%*=.*.+ |

|+=.E =.+ |

| .=.+.o.. |

|.... . S |

|.+ o |

|+ = |

|.o.o |

|oo+. |

+----[SHA256]-----+The “identification” is actually the private key. You should never share it. The public key is appropriately named. The “key fingerprint” is a shorter version of a public key.

Now that we have generated the SSH keys, we will find the SSH files when we check.

OUTPUT

drwxr-xr-x 1 Alfredo 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ./

drwxr-xr-x 1 Alfredo 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ../

-rw-r--r-- 1 Alfredo 197121 419 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519

-rw-r--r-- 1 Alfredo 197121 106 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519.pub3.2 Copy the public key to GitHub

Now we have a SSH key pair and we can run this command to check if GitHub can read our authentication.

OUTPUT

The authenticity of host 'github.com (192.30.255.112)' can't be established.

RSA key fingerprint is SHA256:nThbg6kXUpJWGl7E1IGOCspRomTxdCARLviKw6E5SY8.

This key is not known by any other names

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no/[fingerprint])? y

Please type 'yes', 'no' or the fingerprint: yes

Warning: Permanently added 'github.com' (RSA) to the list of known hosts.

git@github.com: Permission denied (publickey).Right, we forgot that we need to give GitHub our public key!

First, we need to copy the public key. Be sure to include the

.pub at the end, otherwise you’re looking at the private

key.

OUTPUT

ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIDmRA3d51X0uu9wXek559gfn6UFNF69yZjChyBIU2qKI a.linguini@ratatouille.frNow, going to GitHub.com, click on your profile icon in the top right corner to get the drop-down menu. Click “Settings”, then on the settings page, click “SSH and GPG keys”, on the left side “Access” menu. Click the “New SSH key” button on the right side. Now, you can add the title (Alfredo uses the title “Alfredo’s Kitchen Laptop” so he can remember where the original key pair files are located), paste your SSH key into the field, and click the “Add SSH key” to complete the setup.

Now that we’ve set that up, let’s check our authentication again from the command line.

OUTPUT

Hi Alfredo! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.Good! This output confirms that the SSH key works as intended. We are now ready to push our work to the remote repository.

4. Push local changes to a remote

Now that authentication is setup, we can return to the remote. This command will push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

Since Alfredo set up a passphrase, it will prompt him for it. If you completed advanced settings for your authentication, it will not prompt for a passphrase.

OUTPUT

Enumerating objects: 16, done.

Counting objects: 100% (16/16), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (11/11), done.

Writing objects: 100% (16/16), 1.45 KiB | 372.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 16 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), done.

To https://github.com/alflin/recipes.git

* [new branch] main -> mainProxy

If the network you are connected to uses a proxy, there is a chance that your last command failed with “Could not resolve hostname” as the error message. To solve this issue, you need to tell Git about the proxy:

BASH

$ git config --global http.proxy http://user:password@proxy.url

$ git config --global https.proxy https://user:password@proxy.urlWhen you connect to another network that doesn’t use a proxy, you will need to tell Git to disable the proxy using:

Password Managers

If your operating system has a password manager configured,

git push will try to use it when it needs your username and

password. For example, this is the default behavior for Git Bash on

Windows. If you want to type your username and password at the terminal

instead of using a password manager, type:

in the terminal, before you run git push. Despite the

name, Git

uses SSH_ASKPASS for all credential entry, so you may

want to unset SSH_ASKPASS whether you are using Git via SSH

or https.

You may also want to add unset SSH_ASKPASS at the end of

your ~/.bashrc to make Git default to using the terminal

for usernames and passwords.

Our local and remote repositories are now in this state:

The ‘-u’ Flag

You may see a -u option used with git push

in some documentation. This option is synonymous with the

--set-upstream-to option for the git branch

command, and is used to associate the current branch with a remote

branch so that the git pull command can be used without any

arguments. To do this, simply use git push -u origin main

once the remote has been set up.

We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

OUTPUT

From https://github.com/alflin/recipes

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, though, this command would download them to our local repository.

GitHub GUI

Browse to your recipes repository on GitHub. Under the

Code tab, find and click on the text that says “XX commits” (where “XX”

is some number). Hover over, and click on, the three buttons to the

right of each commit. What information can you gather/explore from these

buttons? How would you get that same information in the shell?

The left-most button (with the picture of a clipboard) copies the

full identifier of the commit to the clipboard. In the shell,

git log will show you the full commit identifier for each

commit.

When you click on the middle button, you’ll see all of the changes

that were made in that particular commit. Green shaded lines indicate

additions and red ones removals. In the shell we can do the same thing

with git diff. In particular,

git diff ID1..ID2 where ID1 and ID2 are commit identifiers

(e.g. git diff a3bf1e5..041e637) will show the differences

between those two commits.

The right-most button lets you view all of the files in the

repository at the time of that commit. To do this in the shell, we’d

need to checkout the repository at that particular time. We can do this

with git checkout ID where ID is the identifier of the

commit we want to look at. If we do this, we need to remember to put the

repository back to the right state afterwards!

Uploading files directly in GitHub browser

Github also allows you to skip the command line and upload files directly to your repository without having to leave the browser. There are two options. First you can click the “Upload files” button in the toolbar at the top of the file tree. Or, you can drag and drop files from your desktop onto the file tree. You can read more about this on this GitHub page.

GitHub Timestamp

Create a remote repository on GitHub. Push the contents of your local repository to the remote. Make changes to your local repository and push these changes. Go to the repo you just created on GitHub and check the timestamps of the files. How does GitHub record times, and why?

GitHub displays timestamps in a human readable relative format (i.e. “22 hours ago” or “three weeks ago”). However, if you hover over the timestamp, you can see the exact time at which the last change to the file occurred.

Push vs. Commit

In this episode, we introduced the “git push” command. How is “git push” different from “git commit”?

When we push changes, we’re interacting with a remote repository to update it with the changes we’ve made locally (often this corresponds to sharing the changes we’ve made with others). Commit only updates your local repository.

GitHub License and README files

In this episode we learned about creating a remote repository on GitHub, but when you initialized your GitHub repo, you didn’t add a README.md or a license file. If you had, what do you think would have happened when you tried to link your local and remote repositories?

In this case, we’d see a merge conflict due to unrelated histories. When GitHub creates a README.md file, it performs a commit in the remote repository. When you try to pull the remote repository to your local repository, Git detects that they have histories that do not share a common origin and refuses to merge.

OUTPUT

warning: no common commits

remote: Enumerating objects: 3, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/alflin/recipes

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

* [new branch] main -> origin/main

fatal: refusing to merge unrelated historiesYou can force git to merge the two repositories with the option

--allow-unrelated-histories. Be careful when you use this

option and carefully examine the contents of local and remote

repositories before merging.

OUTPUT

From https://github.com/alflin/recipes

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

README.md | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 README.mdKey Points

- A local Git repository can be connected to one or more remote repositories.

- Use the SSH protocol to connect to remote repositories.

-

git pushcopies changes from a local repository to a remote repository. -

git pullcopies changes from a remote repository to a local repository.

Content from Collaborating

Last updated on 2023-11-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I use version control to collaborate with other people?

Objectives

- Clone a remote repository.

- Collaborate by pushing to a common repository.

- Describe the basic collaborative workflow.

For the next step, get into pairs. One person will be the “Owner” and the other will be the “Collaborator”. The goal is that the Collaborator add changes into the Owner’s repository. We will switch roles at the end, so both persons will play Owner and Collaborator.

Practicing By Yourself

If you’re working through this lesson on your own, you can carry on by opening a second terminal window. This window will represent your partner, working on another computer. You won’t need to give anyone access on GitHub, because both ‘partners’ are you.

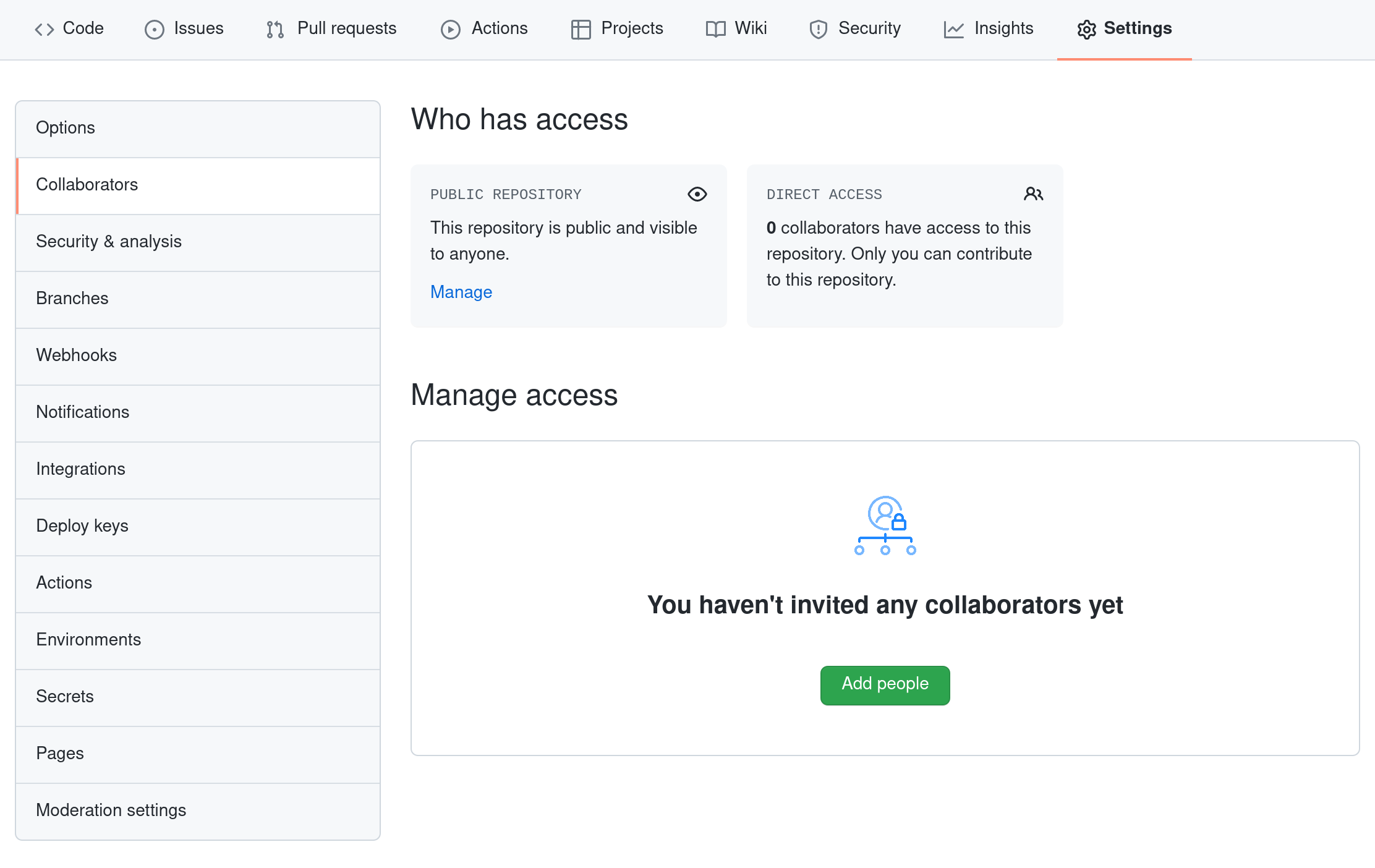

The Owner needs to give the Collaborator access. In your repository page on GitHub, click the “Settings” button on the right, select “Collaborators”, click “Add people”, and then enter your partner’s username.

To accept access to the Owner’s repo, the Collaborator needs to go to https://github.com/notifications or check for email notification. Once there she can accept access to the Owner’s repo.

Next, the Collaborator needs to download a copy of the Owner’s repository to her machine. This is called “cloning a repo”.

We’ll be using a repository listing the locations of people’s favourite pubs, restaurants, cafes and just general favourite places to go. You can find this repository at https://github.com/NOC-OI/favourite-places

To clone the Owner’s repo into her Desktop folder, the

Collaborator enters:

If you choose to clone without the clone path

(~/Desktop/favourite-places) specified at the end, you will

clone inside your own favourite-places folder! Make sure to navigate to

the Desktop folder first.

The Collaborator can now make a change in her clone of the Owner’s repository, exactly the same way as we’ve been doing before:

OUTPUT

name,symbol,creator,comments,lon,lat

Express Cafe,cafe,Vlad,black pudding,-4.081978,52.414381OUTPUT

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 places.csvThen push the change to the Owner’s repository on GitHub:

OUTPUT

Enumerating objects: 4, done.

Counting objects: 4, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 306 bytes, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To git@github.com:NOC-OI/favourite-places.git

9272da5..29aba7c main -> mainNote that we didn’t have to create a remote called

origin: Git uses this name by default when we clone a

repository. (This is why origin was a sensible choice

earlier when we were setting up remotes by hand.)

Take a look at the Owner’s repository on GitHub again, and you should be able to see the new commit made by the Collaborator. You may need to refresh your browser to see the new commit.

Some more about remotes

In this episode and the previous one, our local repository has had a

single “remote”, called origin. A remote is a copy of the

repository that is hosted somewhere else, that we can push to and pull

from, and there’s no reason that you have to work with only one. For

example, on some large projects you might have your own copy in your own

GitHub account (you’d probably call this origin) and also

the main “upstream” project repository (let’s call this

upstream for the sake of examples). You would pull from

upstream from time to time to get the latest updates that

other people have committed.

Remember that the name you give to a remote only exists locally. It’s

an alias that you choose - whether origin, or

upstream, or fred - and not something

intrinstic to the remote repository.

The git remote family of commands is used to set up and

alter the remotes associated with a repository. Here are some of the

most useful ones:

-